Chicago Reader and City Bureau win March Sidney for Exposing Police Union’s Spin After Shootings

Yana Kunichoff, Sam Stecklow, Darryl Holliday of City Bureau, and Robin Amer of the Chicago Reader win the March Sidney Award for revealing that Chicago’s police union has long served as the propaganda arm of the Chicago PD, often misleading the public in the wake of police-involved shootings.

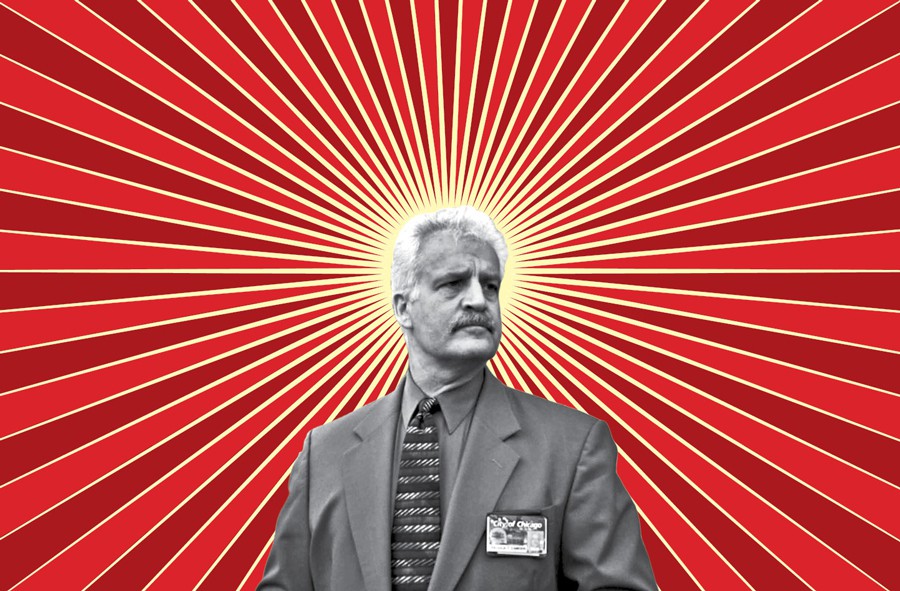

When Laquan McDonald was shot 16 times by a police officer, Fraternal Order of Police spokesperson Pat Camden told the media McDonald was armed with a knife and that the officer shot in self-defense. A dashcam video and an autopsy report would later disprove the police account, but, by then, media outlets had already reported Camden’s version as fact.

Camden disseminated misinformation about 15 of the 35 shootings the union has commented on since 2012, the winners’ investigation found.

Camden would show up at shootings to take the officer’s side of the story and get it out to the media before the Chicago PD could issue an official statement. No other police union takes such an active role in controlling the media narrative.

“The winners have drawn attention the dangers of a relentless 24-hour news cycle where being first is more important than getting it right,” said Sidney judge Lindsay Beyerstein. “The Fraternal Order of Police repeatedly exploited the informational void to mislead the public.”

City Bureau is a new neighborhood newsroom and journalism training lab aimed at regenerating civic media on Chicago’s South and West sides. The Chicago Reader is a free news weekly with a proud history of investigative journalism.

Yana Kunichoff is an investigative journalist and producer based in Chicago who currently works with City Bureau and Scrappers Film Group. She has reported on policing, immigration and education for The Guardian, Al Jazeera America, and other publications.

Sam Stecklow is a freelance reporter. His work has appeared in Gawker, The Awl, Paper, and other publications.

Darryl Holliday is the Editorial Director of City Bureau. He is the co-founder of The Illustrated Press.

Robin Amer is the Deputy Editor for News at the Chicago Reader. She is also the winner of WNYC’s Podcast Accelerator competition, and is piloting her show “The City” with WNYC Studios.

Backstory

Q: What is the role of Chicago’s Fraternal Order of Police when it comes to police-involved shootings?

SS: The role of Chicago’s Fraternal Order of Police is primarily to represent police officers in collective bargaining, offer legal support to officers charged with crimes, and represent the FOP and individual officers in the media.

Their media role has changed in the past year or so. In every police-involved shooting since Laquan McDonald, with one exception, Pat Camden and the FOP have not commented. But up until the police shooting of McDonald in October 2014, the FOP provided preliminary reports to the media, often from the scene of a police-involved shooting, that invariably established a narrative about a police officer fearing for their life after a weapon was pointed at them. A data analysis by City Bureau and the Chicago Reader found that nearly half of those narratives established by the FOP contained misinformation or outright lies.

Q: Who is Pat Camden and what is his MO?

YK: Pat Camden is the spokesman for the Fraternal Order of Police, Chicago’s police union. He was previously a police officer in the CPD, and after that the spokesperson for the police department. Camden joined the FOP in 2011, and would go on to remake the way in which the FOP interacted with the local press. He came from a position of authority within the police department so he already had relationships among the press. He then began speaking to the union reps following a police shooting and giving the police officer’s version of events. In my interviews with Camden, he is firm on not doubting the initial narrative that police officers give at the scene of a shooting, even when, as in the Laquan McDonald case, there is later evidence that their narrative was misleading or incorrect.

Q: Why does the CFOP have such an active role in post-shooting PR, is that normal for a police union?

SS: According to interviews with daily crime reporters and former police officials in eight major American cities – Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Detroit, Baltimore, Milwaukee, Atlanta, Miami, Oakland, and New Orleans – this is not normal for American police unions, which generally comment on larger issues, such as pensions, department-wide reforms, and the like, if at all.

Q: How did you compile your database of fatal police shootings?

YK & SS: We compiled an original database of fatal police shootings in Chicago using a mix of incidents collected from police reports, and existing databases. Among the databases used were ones maintained by the Guardian, the Washington Post, Deadspin, Fatal Encounters, and Truthout. We then checked our figures against those kept by the Internal Police Review Authority, the agency charged with investigating police shootings, and did our best to account for any discrepancy in figures. The information we included was the victim’s name, age, date of death, the neighborhood they were killed in, the initial news stories about their death, and whether the police union or Chicago Police Department gave comment on the breaking news piece.

Q: How did you go about fact-checking the FOP version of events for the shootings?

YK & SS: We compared the initial on-the-scene statements with later reports, generally conducted by the Independent Police Review Authority, law firms representing victims’ families, and media investigations. Our standard of proof for saying that there was a shooting was that two independent sources had raised concerns about the initial FOP narrative - that often included a lawsuit, witness statements on the scene or a report from the Independent Police Review Authority.

Q: You report that police unions around the country have gotten stronger over the years. How is that strength manifest (i.e., more members, bigger war chests, more political influence)?

YK: As police-community relations grew increasingly tense, from the civil rights movement to today, police unions have invested more in lobbying to impact laws and change public perception of policing. The increase in policies such as the war on drugs and fears around urban policing have meant that hiring police officers becomes a political issue, thus raising the stakes for police union’s involvement in policy.

Q: Why have police unions become more powerful while the influence of other unions has waned?

Deindustrialization has lessened the number of people in traditional unions, such as those that have represented autoworkers and other factory employees, and a trend towards right-to-work laws has also undercut union density. Police jobs have been more steady and with the advent of the war on drugs bringing additional funding for urban police departments, their member base and influence has increased.

Q: Camden exploited the informational void that follows every shooting. What can the media do to fill that void on their own and reduce their dependence on questionable sources?

DH: According to Jane Kirtley, a media ethics and law professor at the University of Minnesota quoted in our story, journalists need to be critical of organizations that come “with an authoritative veneer” despite their biased point of view. The Fraternal Order of Police in particular has its own agenda, she argues, and they’re often motivated by “an even stronger incentive to maintain the reputation of its members.” Her advice for journalists is to always make clear when a statement can’t be backed up and explain the limitations of the information available especially, as police accountability expert and professor emeritus of criminal justice at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, Samuel Walker, puts it, when there’s somebody “who now has a record, a proven record, of deliberately giving out false information.”

Q: This piece was the result of a collaboration between City Bureau and the Chicago Reader. How did the two organizations work together?

DH: City Bureau is a journalism training lab aiming to revive media coverage of the South and West Sides of Chicago by training a new generation of young reporters. City Bureau collaborated with the Chicago Reader on this investigative cover story and on several other pieces related to policing and criminal justice in Chicago — the City Bureau team partners with local and national media outlets to provide on-the-ground coverage of the city’s most pressing issues.