Maya Dukmasova wins September Sidney for Exposing Flawed Forensic Science in Chicago

Maya Dukmasova wins the September Sidney Award for her feature in Injustice Watch, “Fake science, faulty methods, misleading testimony,” an exposé of a rogue forensic lab in Chicago that used bogus testing methods to help convict people of driving under the influence of cannabis.

In 2017, 32-year-old Dwan Thompson was pulled over for driving 17 miles over the speed limit. Police found a half-smoked joint in his cup holder. Thompson insists that he last smoked hours before he was pulled over and that he was fine to drive. A toxicologist testified at his trial that his urine sample proved he was over the legal limit to drive. Thompson’s lawyer challenged the veracity of her testimony but he was convicted anyway.

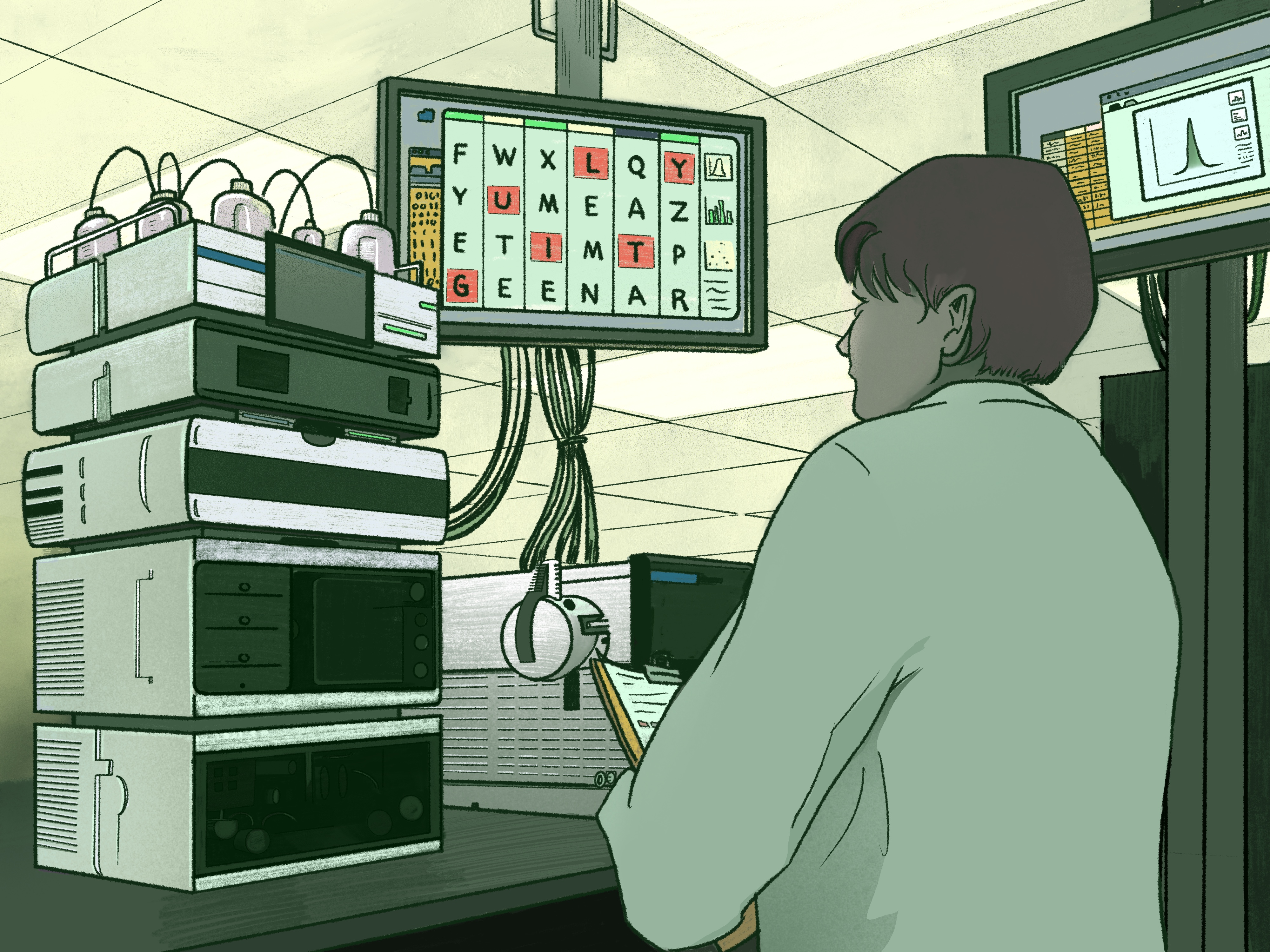

According to Illinois law, the legal limit for delta-9 THC, the active ingredient in cannabis, is 5ng/ml of blood, or 10ng/ml of another “bodily substance,” which the law doesn’t define. Unlike every other forensic lab in the state, the Analytical Forensic Testing Laboratory at the University of Illinois Chicago claimed to be able to determine how much THC was in a person’s urine based on the levels of a THC metabolite. In fact, THC is never present in urine. Furthermore, THC metabolite levels do not prove that the person was high when they gave the sample because metabolites can be excreted hours or days after the drug has worn off.

Injustice Watch identified 2,200 cases in which body fluids were tested for THC by the UIC lab between 2016 and 2024. The lab has been aware of problems with their methodology since 2021, but they continue to perform the tests. Defense attorneys estimate that there are hundreds of people in Illinois with DUI convictions on their records based on the lab’s testing. Dukmasova found two people currently incarcerated in Illinois for DUI convictions secured with the help of the lab, and there are likely more.

The fact that a rogue lab can serve up flawed science in court has disturbing implications. “I was also just shocked to learn about how bad our forensic science oversight system is in Illinois – that basically, there is no system,” Dukmasova said in a Backstory interview.

“This story exposes a major and ongoing miscarriage of justice,” said Sidney judge Lindsay Beyerstein. “The Illinois courts are allowing pseudoscience to ruin people’s lives.”

Maya Dukmasova is a senior reporter at Injustice Watch in Chicago, where she focuses primarily on investigating the Cook County court system. She previously worked at the Chicago Reader and has won numerous local and national journalism awards for her long-form investigative features.

Backstory

Q: How did you find out that something was seriously wrong with cannabis testing for DUIs at this lab in Chicago?

A: I got a tip from an attorney that this lab at the University of Illinois Chicago was testing urine in DUI cannabis investigations and had a problem with their blood testing, too. I immediately understood why the urine testing was concerning. I think that as long as I’ve known about marijuana I’ve known that its byproducts can stay in your urine for a very long time. I wanted to understand how this lab was allowed to do this type of testing to figure out if someone was high while driving.

Q: How are labs supposed to measure whether a driver is impaired by cannabis in Illinois?

A: Illinois’s DUI law is written somewhat vaguely when it comes to the cannabis portion. The law states a driver is over the legal limit for cannabis if there are 5ng of delta-9 THC in their blood or 10 ng of delta-9 THC in another “bodily substance.” The law doesn’t specify urine or any other definition for “other bodily substance.” But delta-9 THC does not show up in urine, only its metabolic byproducts. All other crime labs in the state and that do work for Illinois law enforcement interpreted this law to mean only blood should be tested.

Q: How was Jennifer Bash’s lab trying to measure it, and why did that produce misleading results?

A: UIC’s Analytical Forensic Testing Laboratory developed a protocol for testing whereby they took samples of drivers’ urine, performed some chemistry on them to convert metabolites of marijuana back into the active drug, then quantified how much drug they found and reported it as an amount of THC in the urine. Someone smoking weed at a party on Friday night could wind up pulled over on Monday, suspected of being high for whatever reason, and have their urine collected. The lab’s process would allow law enforcement to claim the person was over the legal limit for THC based on what was in their urine. The lab’s analysis was highly technical and difficult to understand for anyone without scientific training, but to make matters worse Bash would speak to law enforcement and even testify about the meaning of the lab’s results in misleading ways.

Q: How many people were affected by her flawed testing?

A: We know that UIC’s lab issued more than 2,200 reports in which they tested people’s body fluids for cannabis between 2016 and 2024. However, the University is fighting us in court over the release of the reports. Defense attorneys estimate there are hundreds of people around the state who have DUI convictions on their records stemming from the lab’s testing. I found two people currently incarcerated in Illinois whose DUI sentences were secured with the help of the lab, but there are likely more like them.

Q: What impact has your story had so far?

A: The story has prompted quite a bit of coverage in other local media in Chicago and much discussion in online communities focused on forensic science. It has also prompted an inquiry into Jennifer Bash by the American Board of Forensic Toxicology, efforts by Northwestern University’s Center on Wrongful Convictions to find more impacted individuals, and has been cited in Illinois Forensic Science Commission meetings. My biggest hope for impact with this story is that it will not only stimulate the University of Illinois to do the right thing and inform impacted individuals about the lab problems, but also prompt some changes in the forensic science oversight system in Illinois.

Q: Can you give us an overview of your strategy for this very complex investigation?

A: This was the most FOIA-heavy project I’ve ever done. I filed more than 45 FOIA requests, conducted more than 100 interviews, and reviewed about 8,000 pages of public records. Because of the severity of the alleged misconduct by Bash and her boss, the lab director, it was very important for me to have a paper trail for every claim we published. The rumor mill around this lab was pretty vast, a lot of people had known about what was happening there for years. It took some time for me to pinpoint exactly the records I’d need to prove the allegations and document the severity of the problems. Luckily the paper trail was well preserved by the university and I did not run into issues with them denying any of my requests except for the most important one – the lab reports themselves. I was able to secure dozens of them from Illinois police departments, though, and tracked down many impacted people despite UIC’s attempts to keep that hidden. As my inbox was flooded by reams of records and I conducted more and more interviews, a simple timeline was my biggest friend. Every piece of information I was able to document related to the lab and its personnel I organized in the timeline. In the end it made it much easier to identify a clear narrative arc and write the story.

Q: Did anything unexpected happen in the course of reporting this story?

A: I was surprised that Jennifer Bash talked to me, even via email. Her boss, Karl Larsen, declined to comment and I expected the same from her. But I think she did engage in good faith. To this day I still can’t be sure if she truly believes she’s done nothing wrong. I was also just shocked to learn about how bad our forensic science oversight system is in Illinois – that basically, there is no system. This story involves a very small lab, a bit player in the state’s forensic science landscape. If and when the next scandal develops in one of the state’s main crime labs – all of which are run by the Illinois State Police – we are not at all prepared to reckon with it.