These aren’t used cars so much as usury cars….

In a special three-part series, Ken Bensinger of the L.A. Times investigates the wildly profitable but little known world of “Buy Here Pay Here” used car dealerships. These lots cater to a very specific clientele: People with terrible credit who need a car to hold a job.

In part 1, Bensinger explains the Buy Here Pay Here business model: sign, drive, default, repossess, and resell.

Faced with the choice between getting hosed buy a used car dealer and sleeping on the street, buyers will pay any price and accept financing on any terms. The dealers know it. Cars are priced above their Blue Book value and financed at an average interest rate of 20.7%, triple the national average.

Buy Here Pay Here dealerships are only nominally selling cars. Their real business is financing. And because they write their own loans, they are exempt from most forms of regulation. The “Pay Here” part of the name indicates that the buyer delivers payments in cash to the dealership.

You’d think that selling cars on credit to the country’s least reliable borrowers would be an unprofitable business. Not so. The average BHPH dealership turns a 38% profit.

The thing is, these dealers don’t care if customers make their payments. In fact, it’s better if they don’t. These cars come standard with hidden GPS trackers and remote ignition locks for easy repo. If a customer falls behind, the car is seized an resold. Bensinger found that cars were often resold at higher prices the second and third times around.

In part II, Bensinger reveals that Wall Street is in on the racket. (At this point the reader may experience a sinking feeling in the pit of the stomach and an unshakeable sense of deja vu. That’s a common side effect of devastating investigative reporting. Do not be alarmed. Be enraged.)

Financial chopshops have sprung up on Wall Street to cash in on the BHPH boom. Loans originated by BHPH dealers are being securitized, meaning that financial wizards are chopping up these ultra-subprime auto loans and packaging them into securities for investors to buy. Some of these products are rated AAA.

This is the exact scam that led to the subprime mortgage crisis. Bad loans are being repackaged as securities backed by what are surely inflated ratings and pawned off on hapless investors.

These securities will turn into so much worthless paper if the BHPH industry can’t keep all the balls in the air. But neither the securitizers nor the used car dealers care because, they’ll have already made their money.

The third part of the series will run tomorrow. Sidney can hardly wait.

If the word gets out, Occupy the Lot could be the next phase of the Occupy Movement.

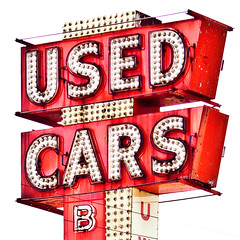

[Photo credit: SeeMidTN.com, Creative Commons; visit SeeMidTN.com on the web.]