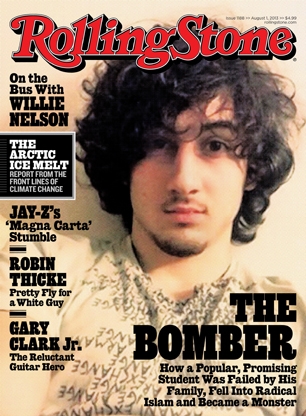

Rolling Stone put a selfie of Jahar Tsarnaev on the cover of their August 1st issue, and all hell broke loose. The headline for Janet Reitman’s cover story reads: “The Bomber: How a popular, promising student was failed by his family, fell into radical Islam, and became a monster.” CVS is refusing to sell it, Mayor Thomas Menino of Boston called the cover a disgrace, and people I’m 99% sure have never read Rolling Stone are loudly threatening to cancel their subscriptions.

Their complaint is that Rolling Stone has glamorized terrorism.

Rolling Stone’s art directors didn’t make this image, Tsarnaev did. It was culled from one of his social media accounts and published in the Washington Post and the New York Times. It’s a self-portrait of Tsarnaev doing his best impersonation of a sensitive, moody rock star, presumably taken around the time he was planning to blow up the Boston Marathon. You can tell it’s a selfshot because Tsarnaev’s right arm is outstretched inside his baggy Armani Exchange t-shirt in the universal symbol for “selfie.” It’s like a million teenage selfshots in which the photographer strains to project an idealized image.

Everyone assumed Jahar was an assimilated American, and what’s more American than wanting to be a rock star? Jahar captured the look better than most. Keep in mind that while Jahar was playing pop idol on the internet, his older brother and future accomplice Tamerlan had sworn off not just rock but all music because he thought music was anti-Islamic.

The shaggy, sensitive-looking photo was one of the many carefully curated images Jahar presented to the world. Janet Reitman’s cover story is a profile of a guy who was everybody’s favorite all-American stoner jock kid brother until he became a terrorist. The central mystery of his story is the discrepancy between appearance and reality. Putting a self-portrait on the cover captures that mystery perfectly. The question isn’t just “how did an innocent little boy grow up to be a big bad terrorist” (which you could ask any terrorist); the question is “how did Jahar fool everyone into thinking he was an innocent little boy until it was too late?”

“Listen,” says Payack, “there are kids we don’t catch who just fall through the cracks, but this guy was seamless, like a billiard ball. No cracks at all.” And yet a deeply fractured boy lay under that facade; a witness to all of his family’s attempts at a better life as well as to their deep bitterness when those efforts failed and their dreams proved unattainable. As each small disappointment wore on his family, ultimately ripping them apart, it also furthered Jahar’s own disintegration – a series of quiet yet powerful body punches. No one saw a thing. “I knew this kid, and he was a good kid,” Payack says, sadly. “And, apparently, he’s also a monster.” [Rolling Stone]

It’s absurd to think that a cover that plainly identifies Tsarnaev as “the bomber,” a follower of “radical Islam” and “a monster,” glamorizes him. Who is that supposed to impress? The two most likely candidates are aspiring terrorists and Jahar fangirls.

Aspiring Islamic terrorists probably regard Rolling Stone as a decadent Western abomination, given its hardline editorial stance on the inherent goodness of music and boobs. They are unlikely to find Jahar’s selfie treatment particularly inspiring.

Of course the Jahar fangirls, the small but creepy subculture of teens in love with Jahar, are swooning over this picture. But they got ahold of it long before Rolling Stone did. Sadly, high profile killers attract groupies. But a magazine can’t program to the lowest common denominator. If you let the reactions of the Jahar fangirls influence your behavior in any way, the terrorists win.