How Online Education Companies Bought America's Schools

Lobbyists for online education companies took the American public school system by storm last year, according to Lee Fang in a special report in The Nation. Education technology companies are playing hardball against teachers’ unions in a bid to cash in on voucher funding for computer-based instruction, especially in Florida:

If [adivsor to former Gov. Jeb Bush, Patricia] Levesque’s blunt advice sounds like that of a veteran lobbyist, that’s because she is one. Levesque runs a Tallahassee-based firm called Meridian Strategies LLC, which lobbies on behalf of a number of education-technology companies. She is a leader of a coalition of government officials, academics and virtual school sector companies pushing new education laws that could benefit them.

But Levesque wasn’t delivering her hardball advice to her lobbying clients. She was giving it to a group of education philanthropists at a conference sponsored by notable charities like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Michael and Susan Dell Foundation. Indeed, Levesque serves at the helm of two education charities, the Foundation for Excellence in Education, a national organization, and the Foundation for Florida’s Future, a state-specific nonprofit, both of which are chaired by Jeb Bush. A press release from her national group says that it fights to “advance policies that will create a high quality digital learning environment.”

Across the country, education entrepreneurs are seeking to replace public school teachers with computer programs, despite the research that shows that virtual education is inferior to traditional teaching. They are getting lots of help from Tea Party politicians on a mission to privatize schools and bust unions.

This eye-opening story was reported in partnership with the Investigative Fund of the Nation Institute.

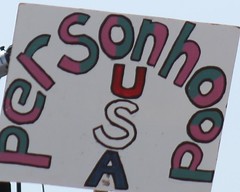

[Photo credit: nebarnix, Creative Commons.]