Saki Knafo wins March Sidney for Groundbreaking Podcast about a Complex Private Investigator Fighting Wrongful Conviction

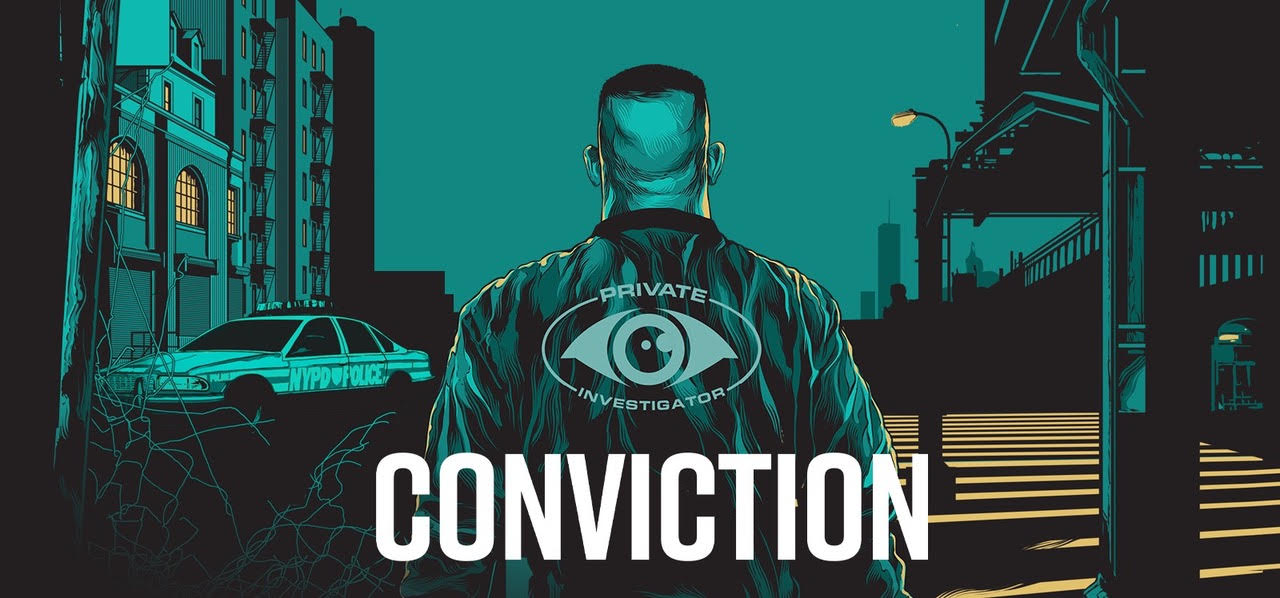

Saki Knafo wins March Sidney for Conviction (Season 1), an investigative podcast series by Gimlet Media in partnership with the New York Times Magazine and Type Investigations.

Conviction is the first podcast to win a Sidney Award. The show is an ongoing series that will feature a new work of investigative journalism every season.

Knafo follows Manny Gomez, a crusading private detective determined to reverse wrongful convictions by any means necessary. Gomez’s clients are young men of color in the South Bronx and he has achieved folk hero status defending his clients against brutal and dishonest cops, but his unorthodox methods and in-your-face manner sometimes backfire.

Gomez styles himself a hero but Knafo discovers that Gomez’s motives are more complex than they initially appear.

“Conviction is a model for investigative reporting in a podcast format,” said Sidney judge Lindsay Beyerstein, “The show combines sophisticated storytelling with investigative vigor to explore moral issues.”

Saki Knafo is a freelance journalist whose work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, GQ, Men’s Journal, The Atlantic, and many other publications. His pieces have also been included in Best American Travel Writing and other anthologies. His New York Times Magazine cover story on Edwin Raymond, a black police officer who sued the NYPD over racial discrimination, received awards from the New York Press Club and the Press Club of Atlantic City.

Backstory

Q: How did you become interested in the story of Manny Gomez and his crusade against wrongful convictions in the South Bronx?

A: A few years ago I wrote a story about a cop who sued the department over what he maintained were racially discriminatory practices, and through that cop’s network I met Manny, a former cop who had himself sued the department for discrimination. I was immediately drawn to him. I’ve always been drawn to people who go against the grain in dramatic ways. Sometimes those people are delusional. Sometime they turn out to be visionaries. Sometimes they’re both. I find that tension interesting. Apart from that, Manny was obviously a character— brash, flamboyant, not afraid to be offensive. And he was a very good storyteller. He’s funny, and he has a whole stockpile of catchphrases and a gift for conjuring the perfect detail. Sometimes as a reporter you have to coax details out of people. Manny was a natural. And although his stories were wild it was not inconceivable that they were largely true. Knowing what I had learned by then about the PD and the way the criminal justice system operates in NY, it wasn’t that hard to believe him when he claimed he’d uncovered nefarious practices.

The main story that Manny told was about fighting a justice system that was running roughshod over the rights of young black and Latino men in the Bronx. It was obvious to me and anyone who was paying attention at the time that this was an important story, whether or not Manny was the most reliable narrator.

I brought the story to the New York Times and also to Gimlet, where I was paired with Meg Driscoll, an audio producer and an amazing reporter. We spent many months interviewing people and going through documents, trying to sort the wheat from the chaff. And while our research didn’t always support Manny’s more flamboyant claims, it still revealed deep and disturbing problems with the system he was fighting.

Q: Manny’s sleuthing resulted in the Bronx DA opening an investigation into police misconduct. What’s the status of the investigation?

A: As of publishing, I didn’t know, and as far as I know nothing has been announced. The District Attorney wouldn’t comment, the Department of Justice wouldn’t comment, and they wouldn’t even confirm they were investigating.

Q: At what point did you realize that Manny wasn’t the uncomplicated hero he (loudly) claims to be?

A: After not that long I realized there was a difference between how he talks about himself and how I and others probably see him. But I didn’t know how important that was or how important that would be to the story.

I began to pay a lot of attention to it after I’d already been on the story for months, because initially I couldn’t really talk to any of Manny’s adversaries. The District Attorney wouldn’t talk and still has never talked, and the Police Department didn’t want to talk. I first spoke to Detective David Terrell on the phone after I’d known Manny for about a year. Then Meg and I sat down with him in person. As I say in the podcast, that kind of flipped everything on its head and forced us to rethink everything we thought we knew.

Then, over the summer, most of the lawsuits against Terrell that Manny had helped generate were dismissed. That raised more questions.

And then in November, Manny lost an important battle. A young man he’d been trying to help went to jail, and the judge laid the blame on Manny. Whether or not that was fair, it felt like a definitive moment. I knew then that the space between how Manny seemed to want to be seen and how I’d come to see him not only couldn’t be ignored but was central to the story.

Q: Based on your extensive investigation and interviews with experts, do you feel that Manny’s investigative tactics cross any professional or ethical lines? And if so, why?

A. As far as I know he operates in the gray area. We spoke with people who believe that he straight up broke the rules but none of them were able to prove it. He certainly walked close to the line, close enough that his enemies didn’t have a hard time making the case that he’d crossed it, and that perception in itself had a profound impact on his story. He paid a price for it and that was important to report.

Q: How has Manny reacted to the podcast?

A: He wasn’t happy with the article and after the podcast came I didn’t hear from him for a while. About a week ago he got in touch. I think he now has mixed feelings. There were things he was upset about, the things you’d expect - parts of the story that don’t portray him in a flattering light - but the podcast has brought him a lot of attention and it seems that much of it has been positive. He tells me he’s heard from a lot of people who say they listened to the podcast and feel he’s doing important work and they’re behind him, regardless of the questions the story raises about his methods and motives, and I’ve heard from people who feel that way too. I should also point out that I’ve heard from a lot of listeners who say they feel empathy for his nemesis, Terrell. As I point out in the podcast, I don’t think this is a story with clear good guys and bad guys. And I think that one of the problems with the criminal justice system is it sorts people into those categories, and not in a careful, thoughtful way. Most people who are convicted of crimes don’t even go to trial. They’re pressured to plead guilty, and the poorer you are, the harder it is to resist that pressure.

Q: What systematic problems did you uncover in the course of your investigation that contribute to young men of color being arrested for crimes they didn’t commit?

A. On the granular level it’s a whole range of problems beginning with stop and frisk, which has been widely covered and is no longer widely practiced in New York. Then there’s the fact that police have traditionally been rewarded by the department to make huge numbers of arrests, which means that they have strong incentives to treat people as criminals even when they don’t have the facts to back it up. Then there’s the blindfold law. Once you’ve been arrested, you don’t have the right to see the evidence against you until your trial is about to begin. If you don’t have an expensive private lawyer who can pull strings and make things happen, you won’t be able to prepare a defense. Your lawyer will probably advise you to plead guilty. The prosecutors will pressure you to plead guilty. Sometimes even the judge will urge you to take a deal. And if you’re stuck in jail because you can’t afford to pay bail, the pressure is even higher. What all this means is that there’s basically two systems of justice in the country: the one we see on TV procedurals — you get arrested, you get a trial. And the system for people who can’t afford a trial, where you’re basically presumed guilty from the outset and relentlessly pressured to surrender the right to defend yourself.

Q: Cop shows lionize police and investigators who don’t “play by the rules.” Is it fair to say that this podcast is a counterweight to that attitude, a brief to consider why we have those rules in the first place?

A. I’m not sure I agree with all of the rules. There’s a rule that says prosecutors are allowed to withhold evidence from defendants until trial beings, and I think that’s a problem and I think the story shows that. But I think there are a lot of rules intended to ensure fairness, and when cops and prosecutors violate those rules, that’s a problem too. There are the mix of rules - rules that allow the powerful to take advantage of those with less power, and rules that are supposed to prevent that. I think what the story shows is that when the powerful have certain incentives and little fear of impunity, they’ll often find a way to screw over the powerless, even if they believe they’re doing the right thing, which I believe most cops and prosecutors do. Sometimes the rules let them do it. Sometimes they bend or break the rules to do it. I’m not trying to chide anyone for breaking the rules. But if the podcast compels people to think about our rules, and why we have them, and which ones should be enforced and which ones should be changed, I think that’s great.