Center for Public Integrity wins January Sidney for Exposing Brutal State Tax Collection Tactics

Maya Srikrishnan and Ashley Clarke win the January Sidney Award for “State tax collectors push struggling people deeper into hardship,” a meticulously reported feature for the Center for Public Integrity. The Internal Revenue Service has a reputation for being relentless, but these reporters discovered that state tax collectors are even tougher than the feds, and their strategies hit low-income residents particularly hard.

“Srikrishnan and Clarke showed perseverance and ingenuity in their reporting,” said Sidney judge Lindsay Beyerstein. “Their ongoing coverage of dysfunctional state taxation has shed light on an important driver of economic inequality.”

Jacques LeBourgeois is among the thousands of people in Louisiana who lost their driver’s licenses in recent years due to state income tax debts — 19,000 in 2023 alone. In Louisiana, you can lose your license for being as little as $1000 in arrears. Maryland has no minimum threshold for denying license renewals.

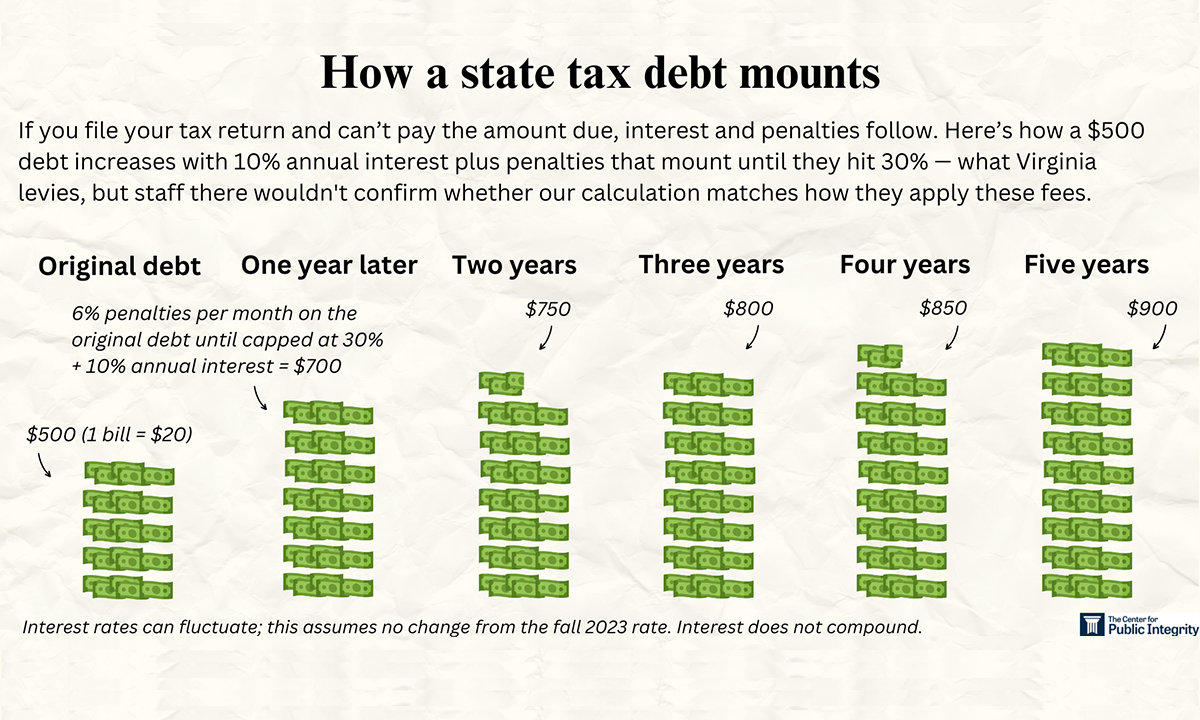

These policies are short-sighted, as most people need to drive in order to work and pay off their debts. Many of those affected are unable to afford accountants or lawyers to navigate the system and find themselves in major trouble over small tax debts that generate spiraling penalties. To make matters worse, some states also rescind professional licenses over unpaid taxes. Ten percent of all massage therapists in Missouri have lost their licenses due to unpaid taxes.

The winners battled bureaucracy to get this story. They wanted basic data from the states on how much tax was owed, how much delinquent taxpayers earned, where they lived, and what enforcement actions were taken against them. These numbers could prove whether the policies were disproportionately hurting poorer taxpayers. Numerous states ignored their inquiries or quoted outrageous prices to supply the data. So, the winners turned instead to tax lawyers, academics and struggling taxpayers to get the story.

Maya Srikrishnan is an investigative reporter with the Center for Public Integrity, where she covers economic inequality. A veteran California-based journalist, she was previously associate editor for civic education at the Voice of San Diego and was a member of the Online News Association’s Women’s Leadership Accelerator in 2021.

Ashley Clarke is the audience engagement editor at the Center for Public Integrity, where she has created innovative partnership models and produced award-winning investigative journalism. She previously worked at NBC4 in Washington.

Backstory

Q: How did you find out about these severe inequities in state tax enforcement?

A: This investigation is part of a series about state taxes we began reporting in 2022. The initial stories focused on the taxes themselves: States typically take a bigger share of household income from poorer residents than richer ones.

But as we talked to policymakers, tax attorneys and advocates across the country, a surprising theme came up in many conversations. States, people kept telling us, tend to be more harsh than the IRS when it comes to tax debt collection.

When we learned that Louisiana suspends driver’s licenses for income tax debts of just $1,000, we set out on a quest to figure out how many other states use similar tactics. Most of all, we wanted to know if these tactics were working as designed or just driving people further into hardship.

Q: Can you give us a 30,000-foot overview of your reporting strategy for this piece?

We knew that data on tax debts by income, ZIP code, amount owed and enforcement action taken could show who was most affected by the status quo. But states did not want to cough that up. After putting in requests with the revenue agencies in Louisiana, New Jersey and New York more than a year ago, we have yet to receive anything.

New York, which doesn’t have mandated deadlines, keeps kicking the can down the road. Louisiana largely ignored us. New Jersey said it would charge $9,760 for the data, then increased the figure to $15,250, and finally ghosted us.

We suspect it’s not just that they don’t want us to know. It’s that they’re not bothering to figure this out themselves. The Louisiana Department of Revenue admitted to us that it doesn’t track its driver’s license suspensions by income range to understand the impact.

As it became clear that not much data would be forthcoming, we pivoted to figure out the impact through other means — academic studies, interviews with more than 30 low-income taxpayer attorneys, deep dives into individual cases.

And once we realized it would be a public service to simply get the states to explain what their collections policies are, we surveyed them. That turned into a months-long slog of repeated reminders, insufficient answers and baffling interactions. (New York and West Virginia thought the public shouldn’t know some or all of this routine information.)

Q: I was shocked to learn that states can deny driver’s licenses for as little as $1,000 in unpaid taxes. How widespread is this practice?

At least nine states, we found, can suspend or decline to renew driver’s licenses because of tax debt. The amount you have to owe varies: In California, it’s more than $100,000, but Maryland sets no minimum amount for blocking license renewal.

That’s not the only collections tactic involving licenses. At least 16 states and Washington, D.C., can suspend or decline to renew professional licenses for unpaid taxes.

We put together a map that shows the states that do one or both.

Q: How do state income tax policies contribute to economic inequality?

A: Suspending driver’s and professional licenses can really cause people to get stuck in the cycle of poverty and hardship. Attorneys who work with low-income taxpayers told us that their clients don’t fall into debt because they’re hoarding money and intentionally trying to break the law, it’s because they got mixed up on complicated tax rules or don’t have enough to afford basic necessities.

Taking their licenses just makes it harder for them to pay up. And it creates no-win situations like those faced by Jacques LeBourgeois, 66, a retiree in ill health who lives alone. Tax debt stripped him of his license for several years, and he had no one to drive him to the grocery store or doctor’s appointments.

Q: Why do some states tie professional licensing to tax payments?

A: Some state lawmakers may think it’s an effective way to force people into compliance. Many taxpayer advocates stressed to us that the practice is counterproductive: If you can’t work, you can’t pay off your debt.

Q: Did anything unexpected happen in the process of reporting this story?

A: We were surprised how difficult it was to get states to explain their hardship programs and their collections policies. Some states were forthcoming, but many offered few details.

It seems like a very basic test of government: Do you have clear and publicly available rules? When it comes to tax debt collection, many states don’t.