Dan Kaufman wins November Sidney for Dynamic Coverage from the U.A.W. Picket Line

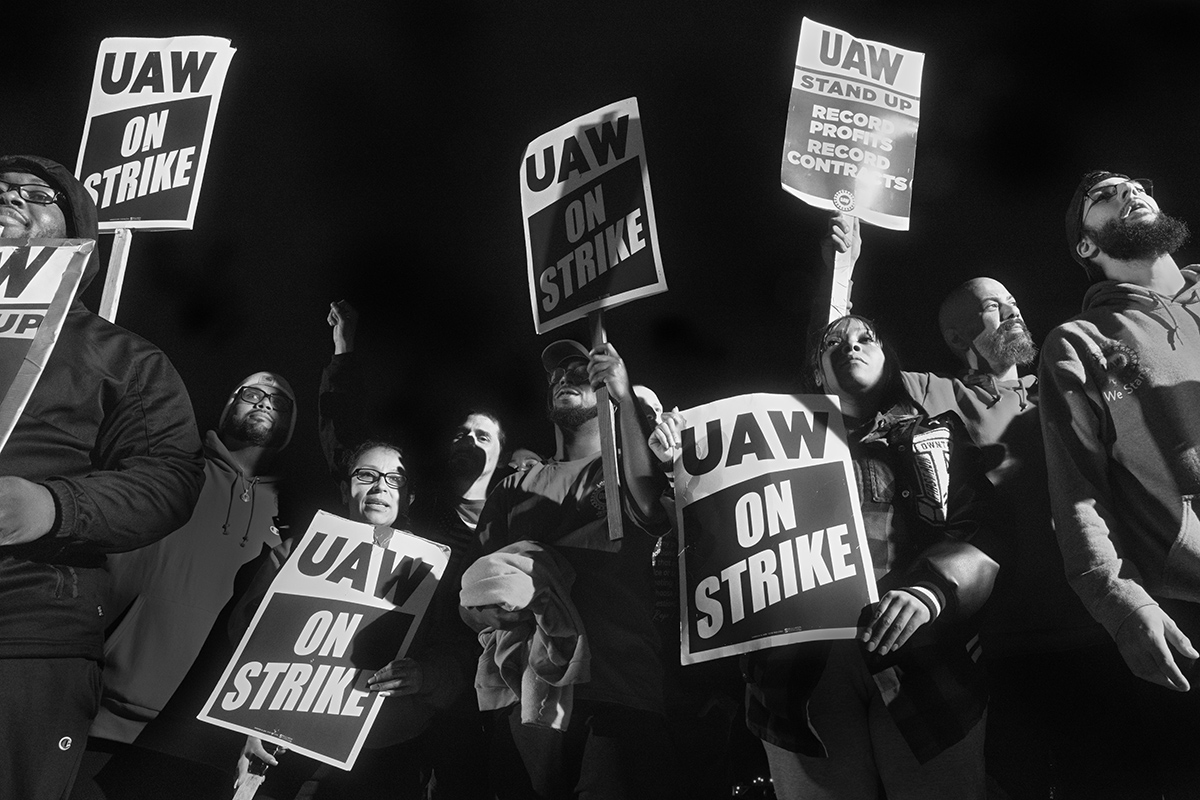

Dan Kaufman wins the November Sidney Award for “Will the U.A.W. Strike Turn the Rust Belt Green?” in The New Yorker. His in-depth feature opens at a meeting of UAW Local 12 in Toledo OH, as members gear up for strike.

The strike will be the first-ever simultaneous action against the Big Three automakers. The union planned to begin with certain carefully chosen plants and reserve the option of widening the strike to more facilities if talks didn’t go well.

The workers of Local 12 were eager to go out first. “We wanted to be the target,” said Local 12 leader Bruce Baumhower. “We think we have the most injustice going on at the shop floor.” Their plant had one of the highest percentages of part-time, low-wage workers with no guaranteed path to permanent employment.

Furthermore, the Big Three auto workers had to make major concessions during the government’s bailout in 2007-2008. The companies have returned to profitability, and the autoworkers have been eager to make up for what they’d lost, including health care benefits for retirees and cost-of-living adjustments.

The auto industry is on the verge of a major shift to electric vehicles. The federal government is pumping billions of dollars into the industry to ease the transition and UAW workers also wanted to make sure that the new jobs making green vehicles are good jobs.

“Kaufman vividly conveys the stakes of this historic strike from the perspective of the rank-and-file,” said Sidney judge Lindsay Beyerstein, “He dramatizes the sacrifices of the workers and their hopes for the future.”

The strike yielded many important gains for workers including higher pay and inclusion of more electric vehicle workers under union contracts. The strike also ended the unfair two-tier wage system.

Dan Kaufman is the author of The Fall of Wisconsin (W.W. Norton), which was published in 2018. He has contributed to The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, and The New York Review of Books among other publications.

The Economic Hardship Reporting Project supported the reporting of this story.

Backstory

Q: Give us an overview of your reporting process for this story.

A: It started with a desire to put the autoworkers on the picket line at the center of the story. From past experiences covering the 2019 GM strike, the closing of a GM assembly plant in Lordstown, Ohio, and the closing of a steel mill in River Rouge, Michigan, I had amassed a lot of background into the issues the workers were facing as well as many sources within the U.A.W., both rank-and-file members and people in leadership positions. That background was helpful in connecting to workers on strike in Ohio and Michigan, and to interviewing them.

I also wanted to weave in an analysis of the larger context for the strike, which needed to include an examination of the labor movement, a distillation of some of the economic challenges facing working-class Americans, the political ramifications of the strike and the underlying causes that contributed to it.

Understanding the history of the U.A.W., both in the recent past and further back, was crucial, especially given the importance of that history to Shawn Fain, the union’s new president. (A recent U.A.W. corruption scandal led to a change in election procedures that allowed Fain, who ran on a reformist platform, to narrowly win; Walter Reuther, the president of the U.A.W. from 1946 to 1970, is a hero to Fain.) To learn this history, I spent time at the U.A.W. archives at Wayne State University, where I was helped enormously by Gavin Strassel, the union’s archivist. I also interviewed scholars like Nelson Lichtenstein, who has written the definitive biography of Reuther.

To illuminate the wider economic and political issues underpinning the strike, I drew on interviews with several economists from the Economic Policy Institute, whose research has focused on the impacts of free trade agreements with low-wage countries, deindustrialization, and the decades-long decline in union density. Earlier reporting across the Rust Belt made me aware of the ongoing fallout, both economic and political, of free-trade deals such as NAFTA which have contributed to the appeal of right-wing populism. To better understand that dynamic and its implications, I interviewed John Russo, an emeritus professor at Youngstown State University who helped pioneer the field of working-class studies, and Marcy Kaptur, a Democratic congresswoman from Toledo who led the fight in Congress against NAFTA in the early 1990s. Kaptur is still in Congress, representing the Ohio district that includes the striking Jeep plant where I spent the majority of my time.

Q: What is a stand-up strike and what did this tactic achieve?

A: The stand-up strike is a new tactic developed by the U.A.W. that targets specific plants rather than having the entire workforce of a company walk out en masse. This strike began with three plants and by the end had expanded to include more than forty-five thousand workers across twenty-two states. The tactic was used to stretch the union’s strike fund, and to ratchet up pressure against the companies when progress stalled. It allowed the U.A.W. to strike the Big Three (GM, Ford, and Stellantis) all at once, which the union had never done before. It was also used to keep the companies off balance. For example, on one occasion the U.A.W. ordered a surprise walkout of a highly profitable Ford plant because it was angry about the company’s lack of movement in negotiations; on other occasions, additional strikes at specific plants were called off at the last minute to reward a company for making concessions. In the end, the stand-up-strike seemed remarkably successful with the caveat that many workers were laid off indirectly because they were working at a place that supplied a striking plant. In those cases, the workers were not eligible for strike pay.

Q: How did the prospect of the energy transition and electric vehicles factor into the UAW dispute?

A: There is significant tension over this transition and rising anxiety for many autoworkers over whether they’ll eventually lose their jobs because of it. Some auto industry experts speculate that electric vehicles will require fewer workers, because these vehicles have no engines and thus have fewer parts. Other experts argue just the opposite, that more workers will be required, at least in the short- and medium-term, because the components that are needed are more complicated even if there are fewer of them.

The U.A.W. is calling for a “just transition,” essentially that new jobs created by electric vehicles should be well-paying union jobs, especially given the enormous funding the federal government is providing to facilitate this green transition. New battery plants are the focus of much of this battle. One battery plant that I concentrated on is in Lordstown, Ohio, right next to the shuttered assembly plant that I documented in 2019. This plant is owned by Ultium, a joint venture between General Motors and a Korean electronics company. Starting pay for workers was $16.50 an hour. (In September, it was raised to $20 an hour.) The plant has also been cited for numerous safety violations. One worker had been killed from injuries sustained on the job, while others have been hospitalized. A U.A.W. safety report found that twenty-two workers had reported incidents to OHSA in the first five months of 2023 alone, a fifty percent higher incidence rate than the union found at traditional G.M. plants. The Ultium battery plant became a poster child for the union’s fears that the transition to electric vehicles will result in a low-wage, low-benefit, and dangerous carveout in the auto industry.

Q: An autoworker told you that “We were promised that future generations would be able to get back what was given up,” she said.” What did she mean by this? And to what extent did the strike get those things back?

A: That worker, a woman named Jennifer Fultz, was referring to the concessions forced on the U.A.W in the aftermath of the 2007-8 financial crash, which was followed by a government bailout of G.M. and Chrysler. U.A.W. workers from across the Big Three had to give up many hard-won benefits including the cost-of-living adjustment, medical insurance for retirees (many of whom retire before becoming eligible for Medicare), and a reduction in break time from six minutes to five. Most significant was the introduction of a two-tiered system in which people hired after 2007 would not receive a pension (it was replaced with a 401k) and would earn roughly half the wage of coworkers hired before the cutoff. At the Toledo Jeep plant, nearly a third of the workforce was still making less than sixteen dollars an hour, almost the same wage a new worker would have made fourteen years earlier. The strike was largely successful at winning back many of these concessions with the major exception of restoring pensions. (The companies did, however, increase their 401k contributions from six to ten percent.)

Q: The autoworkers are back on the job. Can you recap the deal they reached with management?

A: Although the contracts have yet to be ratified, the tentative agreements are an historic victory for the U.A.W. Highlights include twenty-five percent raises over the course of the contract, the restoration of a cost-of-living adjustment, and the end of wage tiers. There were other significant victories too, namely, the right-to-strike over plant closures, a first in the U.A.W.’s history. At G.M., battery plants will be brought under the national agreement with the U.A.W. Workers at Ultium, who voted to unionize last year but have been working without a contract since, will now be G.M. employees and will receive an immediate $6 to $8 dollar-an-hour raise.

It’s worth noting that these agreements have already impacted non-union automakers too. Since they were announced, for example, Toyota raised wages about nine percent. The Japanese automaker’s move highlights the ripple effect of unions on wages overall. Meanwhile, the success of the strike has clearly galvanized the U.A.W.’s leadership. Since the agreements were announced, Fain has stated that organizing non-union automakers will be a top priority. “When we return to the bargaining table in 2028 it won’t just be with the Big Three, but with the Big Five or Big Six,” he said.