Kavitha Surana wins October Sidney for exposing deaths caused by Georgia abortion ban

Kavitha Surana of ProPublica wins the October Sidney Award for “Abortion Bans Have Delayed Emergency Medical Care. In Georgia, Experts Say This Mother’s Death Was Preventable.”

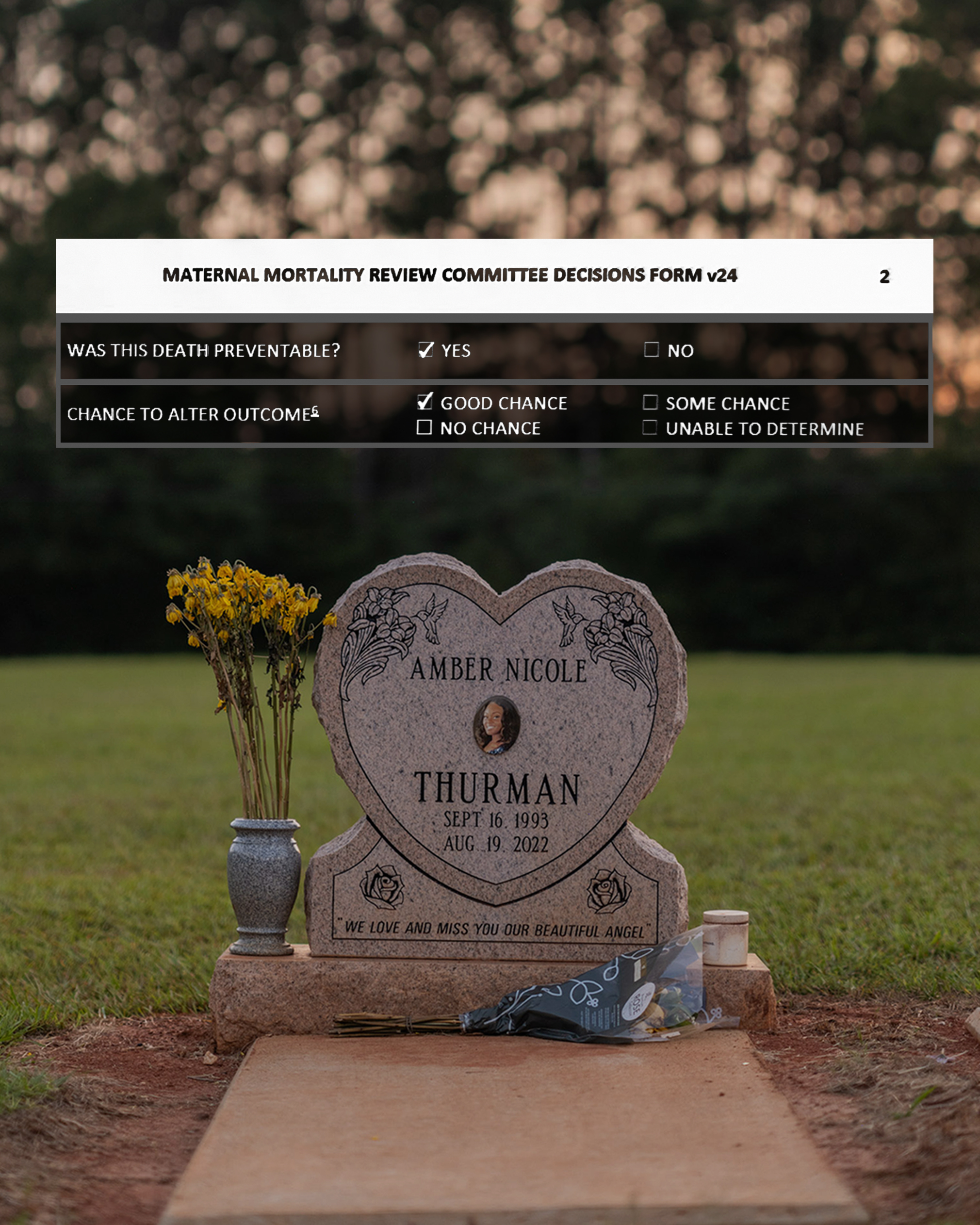

Surana documented the deaths of two women linked to Georgia’s abortion ban, making her the first journalist to document ban-related deaths officially certified as preventable by a committee of maternal health experts. Surana’s coverage had nationwide impact, including a mention by Gov. Tim Walz in the Vice Presidential debate before an audience of 43 million TV viewers.

Amber Nicole Thurman, a healthy 28-year-old medical assistant and single mom, developed a life-threatening infection after a medication abortion. Thurman was bleeding profusely and had even lost consciousness, but doctors waited 20 hours to perform a simple D&C procedure to evacuate the infected tissue from her uterus, even as her condition deteriorated. In such cases, Georgia law forces doctors to stand by until the patient is facing death or permanent injury. Apparently, by the time Thurman was deemed sick enough, it was too late.

Candi Miller suffered from multiple chronic health conditions which, according to her doctors, made it hazardous to continue her pregnancy. She was afraid to go to the hospital after she developed complications from a self-managed medication abortion. Georgia’s law doesn’t specifically exempt women from prosecution for abortions and one Atlanta-area district attorney threatened to prosecute abortion seekers. Miller died at home after days in agony.

“Surana’s investigative skills and sensitive storytelling brought national attention to the human cost of abortion bans,” said Sidney judge Lindsay Beyerstein.

Kavitha Surana is a reporter at ProPublica.

Backstory

Q: How did you go about obtaining the records from the state maternal mortality review committee?

A: The records are confidential so I can’t go into detail on that.

Q: Describe the process of reviewing medical examiner and coroners’ reports to identify potential abortion-related deaths? Is there a database you can search?

A: Every state has different rules regarding what death records are available and open to the public. Georgia is a rare state in that it has a central, publicly available database of death certificates, and we have a reporter on staff who regularly requests that database. You can search it by whether the person was pregnant or recently pregnant. So we used that to look at causes of death that seemed unusual.

Q: Thurman had already induced the miscarriage, and her pregnancy was not viable, why did Georgia’s abortion ban come into play?

A: The hospital and doctors involved in Thurman’s care did not respond to multiple requests for comment, and we don’t know what was going through their minds. But our past reporting has documented how confusion over exceptions in abortion bans have led to delays or denials of care even in dangerous situations, including situations where the fetus was not viable. These laws are written with language that is not rooted in science and don’t correspond to the fast-moving realities of medicine, and they threaten penalties like loss of medical license or a prison sentence of up to 10 years.

Prosecutors have rarely clarified how they would apply the law. Most hospitals have resisted creating formal policies. This has led to the stigmatization of these procedures, and confusion and sometimes misinformation over when doctors can act. Additionally, many states, such as Georgia allow healthcare providers to decline to participate in procedures that are abortion-related. In some situations, such as one we have written about, a team of healthcare providers was needed to perform an abortion procedure, but not all of them agreed they were willing to take on the risk.

Q: If Thurman hadn’t told her doctors that she’d taken abortion pills, as opposed to having a spontaneous miscarriage, would they have had more leeway to save her life?

A: We don’t know the answer. But the way the law is written, it specifies it’s not considered an abortion to remove “a dead unborn child” that resulted from a “spontaneous abortion” defined as “naturally occurring” from a miscarriage or a stillbirth.

Q: Have Georgia Republicans resisted efforts to clarify that the law doesn’t apply to miscarriage care?

A: After our story, Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp released a statement accusing journalists of spreading misinformation about the ban. But he didn’t clarify when the exceptions apply or don’t. For example, a situation that doctors have described confusion over would be when a woman’s water breaks too early for the fetus to be viable. This could be considered a miscarriage in process, because there’s almost no chance the fetus can survive. But continuing to wait until the miscarriage completes naturally increases the chance for sepsis, a deadly infection, to take hold. Can doctors intervene even if there’s still a heartbeat? Doctors have been asking questions like this since the law first passed.

Q: Do you know why the hospital hasn’t given Thurman’s medical records to her family?

A: The hospital asked for more documentation and the family is now represented by an attorney who is pursuing these records.

Q: Did anything unexpected happen in the reporting of this story?

A: It’s always unexpected to be able to see documents that are usually kept confidential from the public.