Wolfe & Liu win February Sidney for Exposing Mississippi’s Modern Day Debtors Prisons

Anna Wolfe and Michelle Liu win the February Sidney Award for “Think Debtors Prisons Are a Thing of the Past? Not in Mississippi,” with data analysis by Andrew R. Calderon, published by The Marshall Project and Mississippi Today. Additional partners include the USA Today Network, the Clarion-Ledger, the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, Mississippi Public Broadcasting and Report for America.

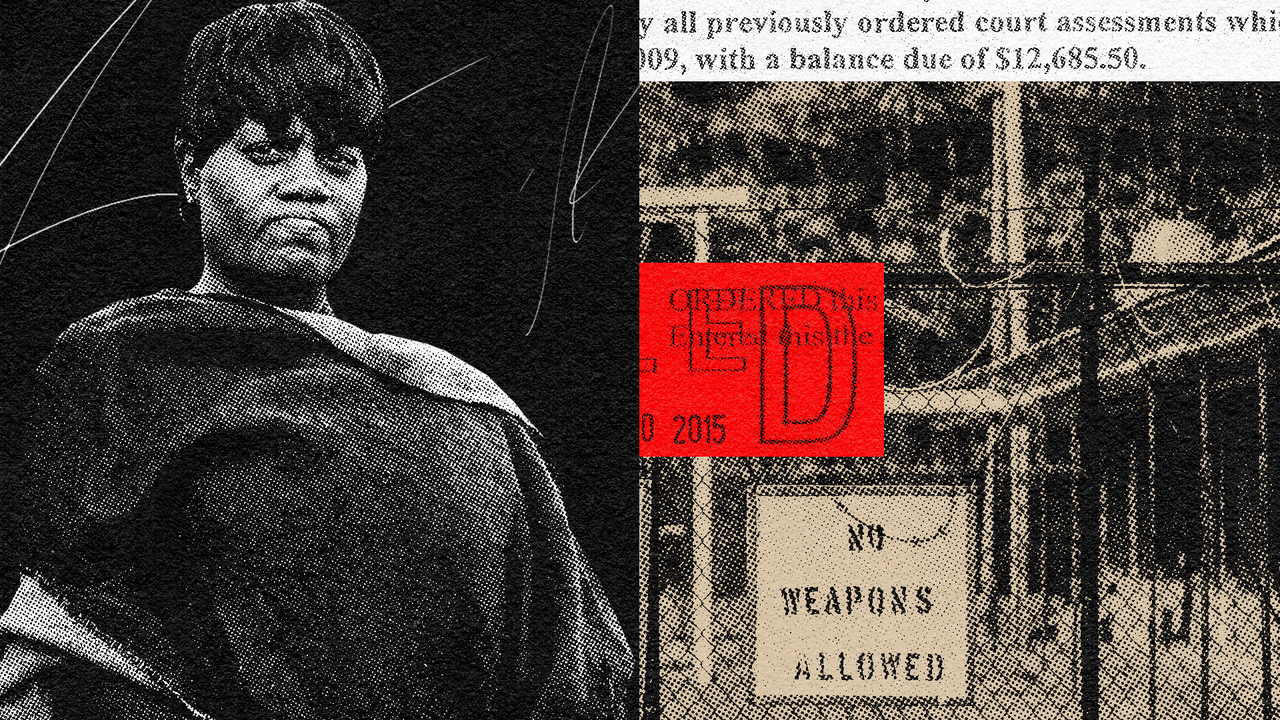

The yearlong investigation revealed that Mississippi confines people with felony convictions to prison-like facilities known as “restitution centers” where they work low-wage jobs for private employers by day and retreat to locked facilities at night, in order to pay off fines, court fees and restitution.

Judges sentence people for as long as it takes to work off their debt, not for a set amount of time. “Residents” have spent up to five years working off their criminal justice debt, plus $11 a day in room and board fees. They sleep seven to a room behind razor wire and endure strip searches for contraband.

“You’re there without an end. You do not know when you’re getting out, when you’re going to be finished,” said Annita Husband, who was incarcerated at a restitution center. “That’s torture.”

Only a quarter of all funds from these so-called “restitution centers” actually go to compensate victims of crime, the investigation found. The lion’s share goes to various fines and fees to courts and the department of corrections.

Black people, poor people and people with addictions are disproportionately likely to be sentenced to a restitution center, Wolfe and Liu found.

“Restitution centers are a form of penal labor that evokes Mississippi’s sordid history of slavery and post-slavery convict leasing,” said Sidney judge Lindsay Beyerstein.

Anna Wolfe, a native of Tacoma, Wa., is an investigative reporter who writes about poverty and economic justice. Before joining the staff at Mississippi Today in September 2018, Anna worked for three years at Clarion Ledger, covering local government and health care. She also worked as an investigative reporter for the Center for Public Integrity and Jackson Free Press. Anna received the Bill Minor Prize for Investigative Journalism in 2018 and 2019 and first place for in-depth investigative reporting from the Mississippi Press Association in 2018 and 2019 for stories on hunger and medical billing.

Michelle Liu has covered criminal justice issues for Mississippi Today through the Report for America initiative since June 2018. She has interned for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and the New Haven Independent. The Institute for Non-Profit News named Michelle’s reporting on the spike of prison deaths in Mississippi as one of the “Best in Nonprofit News” in 2018.

Backstory

Q: How did you learn that people were being forced to work off debts in so-called “restitution centers” in Mississippi?

A: A longtime source reached out in October 2018 about problems his friend was having as a Mississippi state inmate. We could find her, he said, if we visited a local McDonald’s during her shift. It was remarkable enough to discover that inmates in Mississippi were working at private companies — fast-food restaurants and factories — across the state. When we began talking to people who had gone through the program and retrieved their sentencing orders, we learned that they were imprisoned there until they earned enough at their mostly low-wage jobs to pay off every penny the court ordered, amounts sometimes in the tens of thousands of dollars.

Q: Can you give us an overview of the investigative methods you used to get this scoop?

A: We relied on firsthand accounts from more than 50 people sentenced to restitution centers to understand life at the centers. Although the program is publicly billed as an alternative to prison, people we interviewed described the centers as prisons or jails.

For months, the state corrections agency refused to tell us who employs restitution center inmates or give us information about the program. Instead, we started with the first tip we received — the McDonald’s — and worked our way out. At the restaurant, incarcerated workers told us where other restitution centers inmates worked. We left our business cards with employees, catching people before and after their shifts and passing messages through their co-workers.

We also found lists of people at restitution centers from previous years on the corrections agency’s website, which were later removed. We used those and other state data to find and interview more people who were sentenced to the centers. To corroborate their accounts, we drew on court transcripts and other state documents gleaned from more than two dozen public-records requests. And by building a database with the sentencing orders of more than 200 people incarcerated at the centers in January 2019, we found a pattern that matched what we’d heard: judges said most people they sentenced to the centers could not be released until they’d paid off their debts.

Q: Am I understanding correctly that restitution centers are only for criminal justice debts like restitution?

A: Yes. Everyone incarcerated at the centers is paying off debts related to felony-level, non-violent crimes. But “restitution center” is largely a misnomer. Some people we found there were convicted of drug possession and therefore didn’t owe restitution to a conventional victim. Others were paying off far more in court fines and fees than in restitution. In some cases, judges added past-due child support to the debts people had to pay, prolonging their time at these work camps.

Q: Did you talk to any employers who hired from restitution centers? What did they say about their reasons for being part of this?

A: We wrote an accompanying story about the jobs people from the centers work and what employers think about the program, which you can find here. Many of the employers we interviewed believed that hiring people from these centers gave inmates beneficial work experience. Some thought the centers were more like halfway houses. Others told us restitution centers were a reliable form of labor because corrections employees drive the inmates to and from work each day. One employer who managed a fast-food franchise said he would have a hard time running his business without these workers.

Still, the arrangement gives both employers and the state corrections department a significant amount of power over restitution-center workers. People incarcerated at the centers can be punished for refusing to work, encouraging others to refuse work, being fired or violating employer policies.

Q: What did experts tell you about the link between restitution centers and Mississippi’s history of slavery and convict labor.

A: Experts helped us draw a historical throughline between the state’s post-Civil War justice system and this modern-day labor program. More specifically, those we interviewed said the program was akin to the historical system of debt peonage. Alex Lichtenstein, a history professor at the University of Indiana who wrote a book on convict leasing and chain gangs in the American South, said the program was resonant of Jim Crow. Under that system, African Americans arrested for petty offenses would be fined an amount they couldn’t afford. A planter would offer to cover the costs, and the debtor would work for the planter to repay the debt. Often, the threat of being sent to Parchman — built in the early 1900s as a cotton-growing operation and modeled after a slave plantation — loomed when they agreed to work off their debts. “Parchman was the whip or the cudgel,” Lichtenstein told us.

Q: What did you learn from this project that you will carry forward to future assignments?

A: In reviewing more than 200 sentencing orders, we learned how each case and experience is truly unique in the criminal justice system. We are more familiar with the many scenarios and avenues a criminal case may take. This is understanding we can use to shine a light on the complexities of the criminal justice system and provide readers with better context about the realities of modern-day incarceration.