Todd Frankel wins October Sidney for Exposing Drug Company’s Campaign to Keep Narcan From Going OTC

Todd Frankel of the Washington Post wins the October Sidney Award for “How one company profited while delaying Narcan’s drugstore debut,” a deeply reported tale of corporate greed and big pharma dysfunction. As opioid overdose rates surged nationwide, it became critical to put the powerful overdose-reverser, naloxone, in the hands of everyday people who can act fast to save lives.

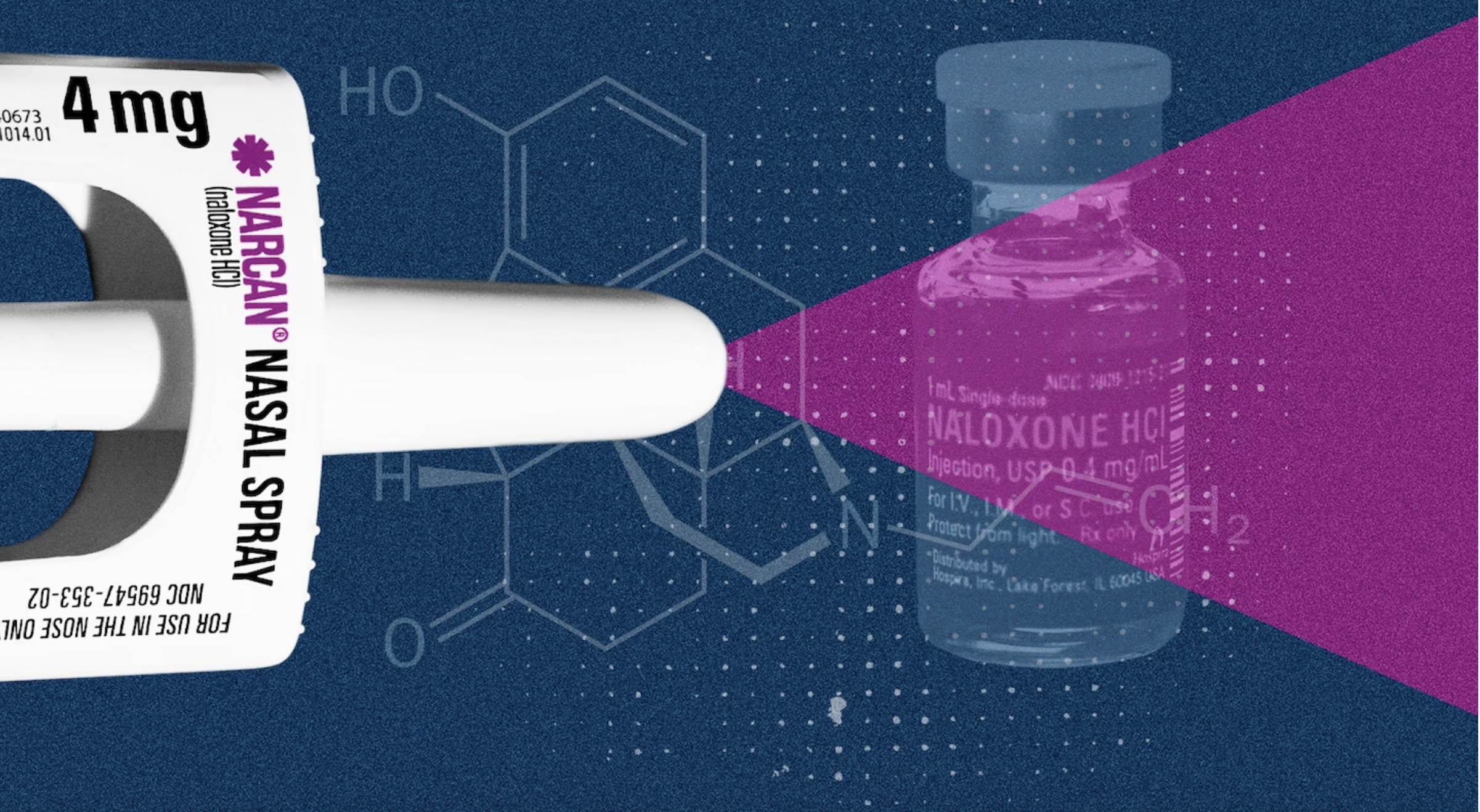

Yet Narcan, a name-brand version of naloxone, only became available over-the-counter this month after five years of stalling by its manufacturer, Emergent BioSolutions. Emergent fought Narcan’s over-the-counter release despite the fact that the federal government absorbed so much of the risk and cost of developing it.

“I think the problem is that the financial model doesn’t appear to be working for the company, so they’re not motivated to do it,” FDA Commissioner Robert Califf said.

For years, Emergent litigated and lobbied to stop the drug from becoming available OTC. A 2-dose box of Narcan spray costs $45 while other naloxone-based injection remedies can cost as little as $2. But Emergent placed their lobbyists on state drug task forces where they were able to pull strings to lock states into lucrative Narcan supply contracts. The company recorded $1.4 billion in Narcan sales over the past four years, while there were sporadic public shortages due to the cost.

“This story holds Emergent Biosolutions accountable for placing corporate greed ahead of human need,” said Sidney judge Lindsay Beyerstein, “Emergent hindered distribution of a lifesaving drug during a worsening overdose epidemic because it was more profitable to do so.”

Todd Frankel is an enterprise reporter on the Financial desk at The Washington Post.

Backstory

Q: Why did the makers of Narcan fight making their version of the drug generic?

A: It didn’t make business sense. Public health officials wanted the shift to reduce barriers to consumer sales, but the company was focused on selling to state and local governments. And going generic meant more competition.

Q: I was shocked to learn that corporate lobbyists are sitting on state drug task forces. Can you tell me more about who they are and how they operate?

A: Emergent had lobbyists on drug task forces in at least three states. Several harm reduction groups complained about the lobbyists having undue influence in the procurement process. States were the biggest Narcan customers. But many harm reduction groups tended to prefer injectable naloxone, not Narcan. So there was a tension there. The company said it was about being able to share its expertise with policymakers. But there appeared to be a conflict of interest to many people. It’s like how doctors today face strict limits on what they can accept from drugmaker’s sales reps – maybe it was above board, but it struck many people as wrong.

Q: Why does Narcan cost so much more than generic versions of the active ingredient, naloxone?

A: That’s a good question. The drug itself is cheap. Its patent expired years ago. The nasal sprayer is simple and off-the-shelf. Even its marketing budget was limited because they were selling to governments, not consumers. Narcan’s makers avoided the mistakes that some other naloxone producers made by charging hundreds or thousands of dollars per dose. Narcan’s price has never been higher than $125 per two-dose package. But for years Narcan had the market to itself, so there was no pressure to lower its price. They’d found a very profitable sweet spot between price and volume. Generics upended that.

Q: Can you explain how the US taxpayer has funded some of the research that made Narcan possible?

A: Naloxone didn’t find a huge market until the opioid crisis exploded in the 2010s. That’s when the FDA begged drugmakers to come up with drugs – treatments, antidotes – to tackle the problem. Opiant/Adapt Pharma, which brought Narcan to market, was unsure if there was even a market for a naloxone product. But federal health officials prodded them, paying for early drug trials and even suggesting to them that they use an off-the-shelf nasal atomizer as the delivery vehicle. The FDA then rolled out the red carpet, clearing regulatory hurdles and basically laying out a roadmap for how to make Narcan an OTC drug. The FDA even drew up a mock “drug facts” box for them to use. So during the entire process the drug company took on very little risk in developing and selling Narcan.

Q: Can we quantify the number of lives lost because of the artificial scarcity of Narcan?

A: It’s difficult. So many factors play into overdoses. But Nabarun Dasgupta, a researcher at UNC, estimated that during a shortage in 2021 there would be at least 12,000 excess deaths that year. And the CDC later reported about 12,000 more deaths in 2021 than 2020 from opioid overdoses. You can see the importance of blanketing communities with naloxone and Narcan.

Q: What did you learn from this investigation that you’ll carry forward to your next assignment?

A: The importance of being curious and just asking questions, even dumb ones. This started with my curiosity about what I called “the fentanyl economy” – a vague notion to look at businesses that are tied in some way to our opioid crisis. I went down blind alleys, like the potential diversion of veterinary drugs. I got increasingly interested in Narcan after talking with some very smart people who were on the epidemic’s front lines.