Beth Schwartzapfel Wins June Sidney for “The Great American Chain Gang”

Beth Schwartzapfel wins the June Sidney Award for “The Great American Chain Gang” a feature in The American Prospect that explores a vast but little-known workforce inside the U.S. prison system, where 870,000 inmates work full time with practically no rights at work.

The median wage in state prison is 20 cents per hour, and three states require prisoners to work for free.

Low wages keep prison budgets down, but the costs are shifted to taxpayers in other ways. Nearly three million children have a parent behind bars. Prisoners with full-time jobs may barely earn enough to buy stamps to write to their kids, let alone support them. Families with a parent behind bars are 50 percent more likely to use Medicaid and twice as likely to use food stamps.

A typical prisoner goes to jail owing hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars in fees for court costs, booking fees, and other prison-related charges, which are difficult to pay off on a prisoner’s meager wages. Inmates are routinely sent back to prison for failure to pay off these debts.

“Prison labor may seem cheap, but the cost is high when prisoners are unable to send money home to support their children,” said Sidney judge Lindsay Beyerstein.

Beth Schwartzapfel is a freelance journalist specializing in long-form and narrative nonfiction. She covers a range of subjects but has a particular interest in the criminal justice system. In addition to the American Prospect, her work has appeared in Boston Review and Mother Jones.

Backstory

Q: What sparked your interest in the labor rights of prisoners?

A: Years ago I did a story for The Nation about the Prison Industrial Enhancement, or PIE, program, which allows private companies to set up factories inside prisons with inmates as employees. It’s a very controversial program, for many reasons. Given the direct link between inmate labor and corporate profits, the incentive to exploit workers is high; and competing firms say there’s no way they can compete with companies that participate in the program. Still, PIE only accounts for about 5,000 inmates–less than 1% of the total prison population–and I thought, what is everyone else doing?

Harvard sociologist Bruce Western has done a lot of work on the economic impact of incarceration on communities of color; he found that excluding prisoners from employment statistics skews our picture of unemployment. If you include prisoners, and count them as unemployed, the already-dismal employment rate of young black men without a college education plummets fifteen percentage points, from 65% to 50%. I was–and still am–stunned by this information. But then I thought, wait a minute: Inmates aren’t really jobless. It’s just that no one is counting their jobs.

Q: Historically, unions have had an uneasy relationship with prison labor. Can you tell us more about that?

A: Well, the first issue is that prisoners have no legal right to organize. They’re not protected by the Fair Labor Standards Act, so prisons can–and do–quash any attempts to demand changes in working conditions, increases in pay, etc. But a deeper complication is that free-world workers often feel inmate workers are undercutting their wages and stealing their jobs. So unions, in a sense, have to choose where their loyalties lie, and some have historically seen inmate workers as unwelcome competitors. But one of my sources, Thomas Petersik, an economist with CURE, told me this is a false dichotomy: “Organized labor has huge built-in motive to keep this thing honest,” he told me. Petersik thinks unions should be auditing prison workplaces, not the National Correctional Industries Association (the industry group currently responsible for auditing many prison work programs). “We need incarcerated workers to be part of bargaining units. They should be in the same unions that you or I would be in.” Then, when they are released and look for similar work on the outside, says Petersik, they can maintain their union ties. “This is a huge opportunity for organized labor to gain membership.” I should also point out that shortly after the issue closed, a group of prisoners in Alabama went on strike; their complaints were wide-ranging, including living conditions and food, but they specifically pointed to the exploitative nature of the state’s inmate labor system. The strikers’ efforts were supported and publicized by the IWW.

Q: How many prisons did you study in the course of reporting this piece?

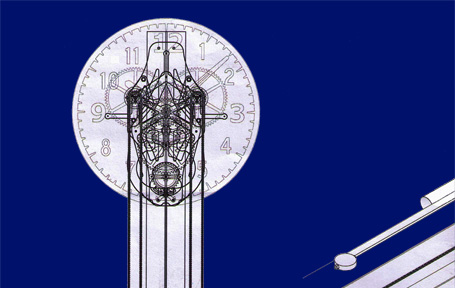

A: I looked most in-depth into two states’ correctional industries programs: North Carolina’s and Tennessee’s. This was sort of an accident, actually. I attended the 2013 National Correctional Industries Association annual conference; it was held in North Carolina, and so that state hosted tours at their metals shop–this is how I got to see the inside of the shop and where I met “Joshua,” the inmate clockmaker in the story. Also at the conference I saw a presentation by one of the marketing people from TRICOR, Tennessee’s program. Aside from the in-depth look at these programs in particular, I studied the system more broadly; I spoke to economists, former inmates, lawyers, directors of other programs, etc. I also read some legal rulings, including some landmark judgements in Washington state and Arizona, which gave me some insight into those states’ programs.

Q: You got remarkable access to inmates and programs. How did go about it?

A: When I saw that there was an industry association for people who run these correctional industries programs, I decided I had to attend their annual conference. So I just logged onto their website and signed up. There was a box where you’re supposed to put your affiliation, but I just left it blank and no one asked any questions. To register for the tour, you had to be an NCIA member, so for something like thirty bucks, I became a member, no questions asked. I thought I might be able to get away with going to the conference unnoticed, but it became pretty clear right away that wasn’t going to be possible. People were super friendly, and “What Department are you with?” or “What state DOC are you from?” was typically the second question they asked after your name. I didn’t feel comfortable lying, so I just said I was a writer interested in the work people do when they’re incarcerated. People seemed more surprised than defensive.

The thing is, I went into that conference with the misconception that nobody there cared about the rights of inmates, that these guys were no better than jailers, that none of them thought of inmates as human beings, only as a cheap source of labor. But I was pleasantly surprised to discover that most everyone I met was acting in good faith. They care deeply about the inmates they work with, and believe in these work programs as an effective, powerful form of rehabilitation, which in a lot of cases they are. So what I thought was going to be a “gotcha” moment turned out to help me understand the landscape with a lot more nuance.

I was lucky that on our tour of the Brown Creek facility, we lingered at “Joshua“ ‘s workstation long enough that I had a chance to ask his name. (Though the director heard me ask and immediately said, “no names!”) When I got home, I looked him up and I sent him a letter, and he sent me an incredibly detailed and thoughtful reply.

Q: Was there anything you wish you could have included in “American Chain Gain,” but had to leave out?

A: There was so much! Here’s one example: When I was at the NCIA conference I went to a brand-marketing panel where Rip Young, an official from TRICOR talked about a marketing push they had done to generate support among legislators for their Cook-Chill facility, in which inmates prepare, process, and package food, mostly for distribution to prisons around the state. It brings in between $12 and $15 million annually, a significant portion of TRICOR’s $35 to $38 million in yearly sales. “But because it’s such a large part of our business, everybody wants a piece of it,” Young told the (friendly) audience. “The private sector wants to take it from us. The legislators want to mandate that we lower our costs at a certain rate. Everyone is trying to do something to influence how this business operates for us.” So they came up with this marketing campaign: a slick sepia-toned pamphlet, plans to visit legislators with a little TRICOR lunchbox, packed with the pamphlet and a brownie baked by inmates in the facility. I was really struck by this because it so goes against the standard line by correctional industries people, that they do not compete with private-sector companies. I wanted to include it as a case study in the story, but when I called TRICOR to find out which private-sector businesses were aiming to compete with Cook Chill for food service contracts, Julie Perrey, the organization’s Chief Networking Officer, told me that has “never happened,” and that, in fact, they had called off the campaign Young was talking about. When I pressed for more details—what aspects of the campaign had been called off, and what had changed since Young’s presentation—I was told that TRICOR had never faced private-sector competition, that Young is no longer with TRICOR, and that Perrey really didn’t know what he had been talking about.

Another line of inquiry there just wasn’t space or time to pursue is, OSHA provided me with a searchable database of all the complaints made to OSHA from correctional facilities in the last number of years. There were many, many cited violations, but the database only gives violation codes, and these translate to pretty vague information; it was almost impossible to tell from the information in the database whether a violation was something along the lines of failure to post a safety sign, or exposure to toxic dust. I really wanted to (still want to) submit a stack of FOIA requests to try to get more information about all these violations. I suspect, but have no way to prove at this point, that the toxic electronic waste (e-waste) recycling program that was finally uncovered in 2010 was only one example of many dangerous prison workplaces.

Q: What would happen to the criminal justice system if prisoners earned minimum wage for their work?

A: Honestly, the whole thing would shut down. The work has to get done, but they can’t afford to pay for it; corrections budgets are already bursting at the seams, and that’s in the current system where inmates are paid pennies an hour, if anything, for their work. After the 9th Circuit ruled in Hale v. Arizona that inmates should be paid minimum wage, Harry Reid commissioned a GAO report to find out what this would actually look like. After extensive research, the GAO found that “If the prison systems we visited were required to pay minimum wage to their inmate workers and did so without reducing the number of inmate hours worked, they would have to pay hundreds of millions of dollars more each year for inmate labor.” In the report, prison administrators threatened that minimum wage would mean “large-scale cutbacks in inmate labor,” but that threat rings hollow. Someone needs to prepare and serve the food, clean the cellblocks and the bathrooms, maintain the grounds, etc. You’re either going to pay inmates or you’re going to pay someone else, but if you want to keep the prison open, the work has to get done.