Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting Wins February Sidney for Exposing No-Jail Jailers

R.G. Dunlop and Jacob Ryan of Louisville Public Media’s Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting win the February Sidney Award for exposing an outrageous system of patronage with their story “Only in Kentucky: Jailers Without Jails.”

Due to a quirk of the state constitution, 41 counties still have an elected county jailer, despite having shuttered the county jail. Anyone over the age of 24 can be a jailer, a job that requires only 40 hours of training and confers the right to carry a gun and make arrests.

Some of these jailers-without-portfolio earn full-time salaries despite having no office, no schedule, and no official duties of any kind. Legally, jailers are supposed to act as bailiffs in court, but not all of them do, and the local courts are rarely busy enough to make bailiff duty an all-consuming responsibility.

Some no-jail jailers have retinues of deputies on the public payroll, including members of their families. The whole system costs these counties, which include some of the poorest parts of the country, about $2 million a year.

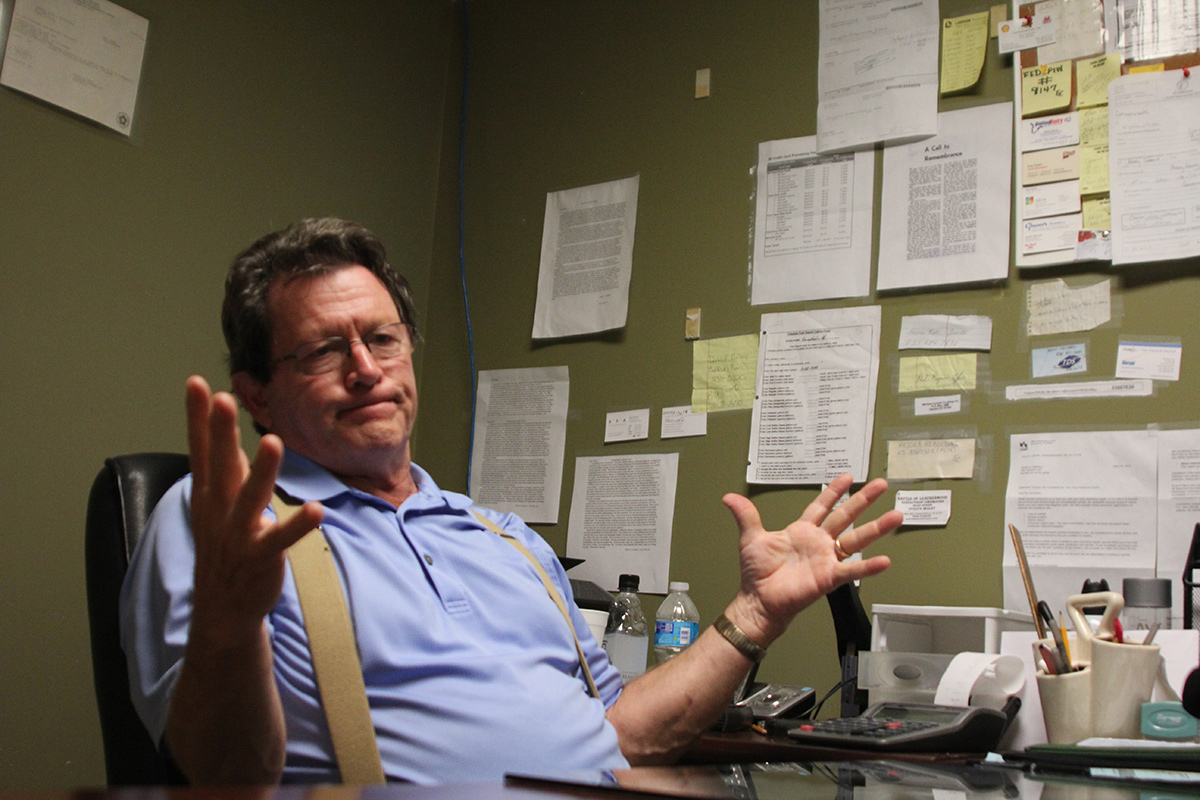

Dunlop and Ryan set out to interview all the no-jail jailers. They caught up with one of them on the golf course and another at home watching cartoons. They found that some of them have enough free time to work second jobs.

The reporters exposed a system that was virtually unknown to the general public. Their coverage sparked widespread public outrage. Since the story ran, one bill has already been introduced in the Kentucky state legislature to reign in the jail-less jailers and another one is expected to be introduced soon.

“This story exemplifies the best of local news reporting,” said Sidney judge Lindsay Beyerstein, “Dunlop and Ryan took on the entrenched power structure and won.”

R.G. Dunlop is a journalist with The Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting. Prior to joining KyCIR, he was a reporter and editor for The Courier-Journal in Louisville. He is a graduate of Miami University and Northwestern University.

Jacob Ryan is the urban affairs reporter for WFPL, Louisville’s NPR news station. He is a Kentucky native and moved to Louisville in 2013. Covering issues ranging from transportation, public safety and housing, he looks to provide residents from all of Louisville’s unique neighborhoods with useful information that can boost their quality of life. He is a graduate of Western Kentucky University.

Backstory

Q: How did you become aware that Kentucky has these jailers-without-portfolio?

A: In the process of reporting other stories about Kentucky’s criminal-justice system, we became aware that many counties in the state had elected jailers with no jails to operate. We started making some inquiries and the numbers of counties, along with the dollar figures, grew quickly. We decided it was something worth spending time and resources on. It also helped that our newsroom, which was launched about 18 months ago, received a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Q: Some of the counties with these jail sinecures are very poor. Can you give us a sense of the burden that these do-nothing offices put on the budgets of these counties and the impact that’s having on ordinary people?

A: Many Kentucky counties with jailers but no jails are located in the eastern part of the state, which is one of the poorest regions in the U.S. Paying salaries (and, in some cases, benefits) to no-jail jailers and their deputies represents a significant financial drain on some of those counties. Partly as a result of these questionable expenses, the provision of basic services for county residents can be compromised.

Q: Describe the impact of your reporting.

A: One bill has been introduced in the legislature, seeking to abolish the office of jailer in counties without jails. Another bill is expected to be introduced soon. It would eliminate no-jail jailers’ salaries and compensate those jailers only for work they can show was actually performed. Even the Kentucky Jailers Association, typically a strong advocate for jailers, has stated publicly that changes need to be made to ensure that jailers are more accountable.

In addition, our stories about no-jail jailers have given greater visibility to an issue that previously was virtually unknown to the general public.

Q: What has to happen in order for these offices to be abolished?

A: The Kentucky legislature would have to act to abolish the office of any no-jail jailer. But other measures short of abolition can be taken to increase accountability (see answer to #3).

Q: Was there anything you wanted to include in the story, but had to leave out?

A: The online version of the story, http://kycir.org/2015/01/02/only-in-kentucky-jailers-without-jails/, contained all of the information we considered relevant. Our newspaper partners ran abbreviated versions of the story. These versions appeared in the Louisville, Lexington and Cincinnati markets, among others, and though considerably abbreviated, still included the essential elements of the story.

Q: Have you gotten pushback from anyone in the community for your coverage?

A: Actual “pushback” has been nonexistent because the stories were fact-based and so far have been unchallenged. A few jailers mentioned in our stories have called to complain about what they thought was an incomplete representation of their activities; they had read only the abbreviated version in some of our media partners’ publications. But their concerns generally were addressed by discussing and directing them to details of the full-length stories published on our website.

Q: What does it say about Kentucky politics that jail-less jailers could flourish for so long in plain sight without anyone saying anything?

A: Jailers are an entrenched part of the local political structure across the state. The office of jailer is a popular one in Kentucky. Primary elections routinely attract a half-dozen or more candidates, perhaps in part because the job is perceived at least by some as low-stress and accompanied by a decent (or better) salary.

Several sources quoted in our articles told us that significant change would be challenging, due to the influence that jailers and their association wield in local and state government. For a variety of reasons, including but not limited to political influence, many issues of importance remain out of public consciousness. We believe that a key function of investigative reporting is to bring these issues to light.

Our work concerning jailers is ongoing, and will continue as long as we think there are matters of public interest that need to be addressed.