Jesse Coburn/Streetsblog win July Sidney for Exposing the Black Market in “Ghost Tags”

Jesse Coburn of Streetsblog wins the July Sidney Award for a series exposing the shadowy world of fake license plates, known as ghost tags, and highlighting a brave gig worker turned whistleblower.

Coburn uncovered a vast underground economy. Unscrupulous operators exploit lax laws in states like New Jersey and Georgia to print hundreds of thousands of ghost tags, which they sell on the black market. Temporary paper tags are meant for newly-purchased vehicles, but they’re being printed and sold to unlicensed drivers and/or unregistered vehicles, often by ghost dealerships that may not even sell cars. “Dealers” at a single address in New Jersey printed 136,000 temp tags in 2021, despite having no cars displayed for sale.

Drivers are using ghost tags to get away with everything from unpaid tolls and tickets to lethal hit-and-run accidents, robberies, and shootings. In New York City, 25 people were killed in crashes involving temp tags in 2021 and 2022.

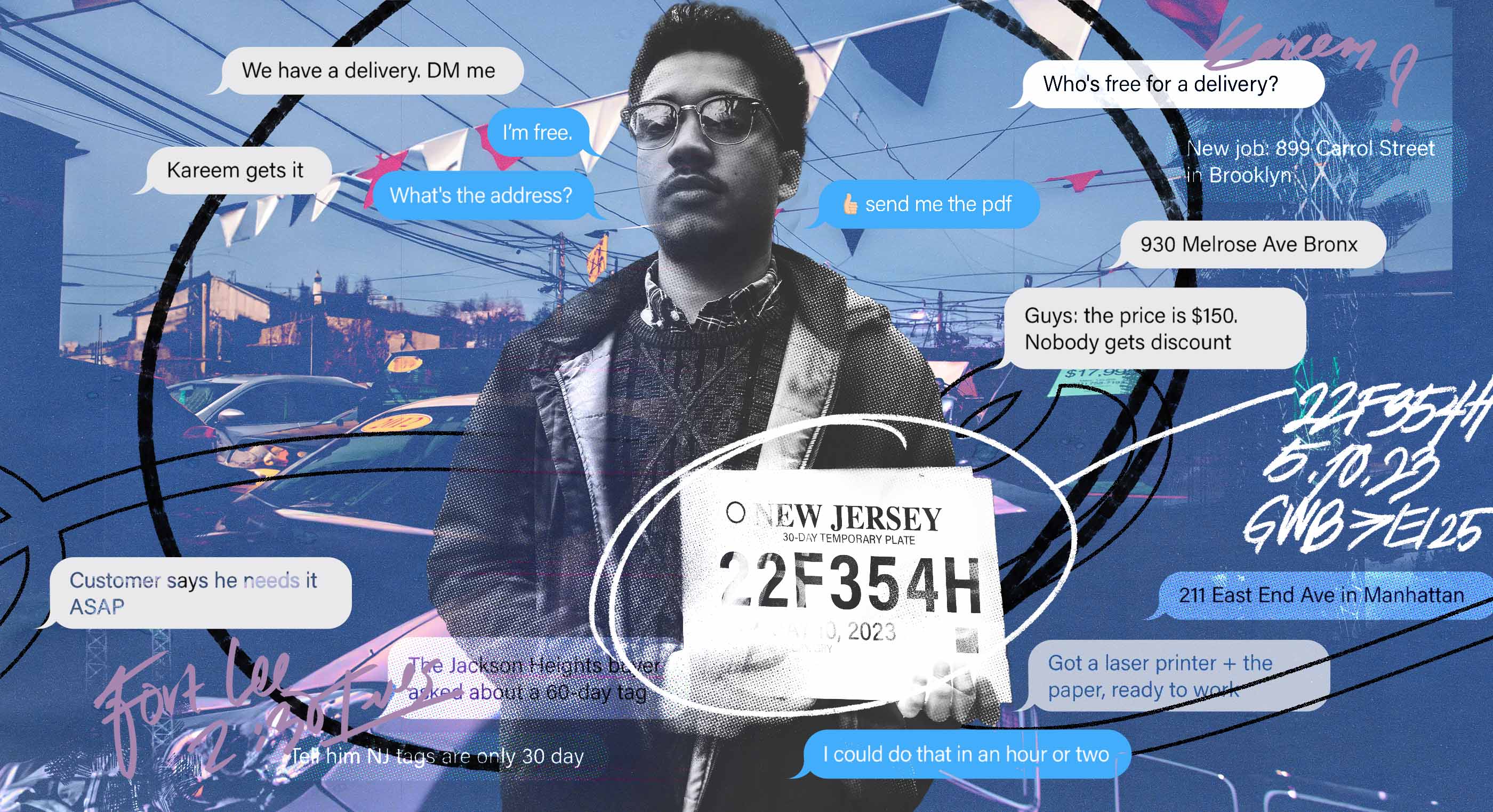

The most recent installment in this series, co-published with Motherboard in June, tells the story of Kareem, a young gig worker who turned whistleblower and exposed the inner workings of a ghost tag ring. Earlier installments were co-published with the New Jersey Monitor.

The series has already had considerable impact. Legislators in New York City and New Jersey have proposed legislation to curb the ghost tag trade by cracking down on sham dealerships.

“The Sidney judges were impressed with the high quality and sheer tenacity of Coburn’s reporting,” said Sidney judge Lindsay Beyerstein, “Kudos to Streetsblog for investing in local investigative reporting.”

Jesse Coburn is an investigative reporter at Streetsblog. He has also reported for the New York Times, Newsday, the Baltimore Sun, Harper’s, and Foreign Policy. His reporting has received awards from the Silurians Press Club, the Sigma Awards, the Overseas Press Club Foundation and the Casey Feldman Foundation.

Backstory

Q: How did you become aware of the ghost tag epidemic?

A: During the COVID-19 pandemic, I started noticing tons of cars in my New York City neighborhood with paper temporary license plates. Virtually all of them were from out-of-state, particularly from Texas, Georgia, and New Jersey. This struck me as odd. You only get a temp tag when you buy or lease a car. It seemed implausible that so many people had just bought cars in, say, Georgia and all happened to drive to the same residential neighborhood in New York City. Once I started looking into it, I learned that wasn’t the case at all. New Yorkers were buying temporary tags illegally—either real tags sold by unscrupulous car dealers or imitations sold by counterfeiters.

There had been great reporting on the issue in Texas, but almost none in New Jersey or Georgia. And while there had been some reporting on the issue in New York, it was mainly driven by law enforcement press releases touting “crackdowns” on drivers using fake paper license plates. No one was talking about where these things were coming from. So I decided to explore the pipeline of tags flowing from New Jersey and Georgia to New York City.

Q: Public records played a huge role in this story. Can you give us a run-down of the records you used and your overall records strategy?

A: I was most interested in real temp tags being sold illegally, as they’re official government documents that presumably should be safeguarded against fraud. So I began submitting public records requests, and eventually obtained comprehensive databases of temp tags issued by licensed used car dealerships in New Jersey and Georgia since 2019. The data told the story. In New Jersey, for example, there was a huge spike in the number of tags issued statewide in 2020 over 2019, and again in 2021 over 2020. It was clear why: no-name dealerships suddenly started printing thousands, even tens of thousands, of temp tags in a year—way more than the average dealership. Further reporting showed some of those dealerships had no other discernible business activity.

The databases also revealed that much of the unusual temp tag activity originated in just a handful of locations: strange office buildings and warehouses that looked nothing like car dealerships but that each served as the official business address of dozens or even hundreds of used car dealers. Business records helped me determine that many of these dealerships were run by New Yorkers.

To figure out what regulators were doing about all this, I requested records on penalties that New Jersey and Georgia had meted out to used car dealers for violations in recent years. This yielded another key finding: when auditors were catching dealers fraudulently issuing tags, they typically imposed minuscule fines. In New Jersey, a $500 fine was standard. Some of the dealerships were printing tens of thousands of tags in a year—worth millions of dollars on the black market. A $500 fine is hardly a deterrent.

Last, court records helped me find people caught driving with fake or fraudulent paper license plates, who explained to me the appeal of the tags: they provide cover while driving without car insurance, evading tolls, or committing more serious crimes on the road.

“Duped,” our latest story, involved more varied source material, including Telegram chat logs, screenshots of Zelle payments, and foreign-language classified ads. Putting those disparate pieces together made it possible to identify who appeared to be running one particular illegal temp tag business that had dozens of couriers delivering tags in the New York metro region.

Q: If you had to pick one statistic that conveys the sheer scope of the ghost tag problem, what would it be?

A: Used car dealers registered to a single address in southern New Jersey printed more than 136,000 temporary license plates in 2021. On paper, that means those dealers sold or leased 136,000 cars that year—which would be far and away the most of any dealer location in the state. But the facility is a desolate-looking cluster of warehouses that never seems to have cars displayed for sale. I tried to visit the compound — supposedly a bustling site of retail car sales — and was not even allowed inside the gate.

Turns out that dozens of dealers registered to the address have issued temp tags illegally. And there are many other facilities like it in New Jersey and Georgia, all cannily designed to just barely comply with modest state standards for what qualifies as a used car dealership. New Jersey has known about suspicious activity at these so-called multi-dealer locations for years but has failed to rein them in.

Q: Tell us about the impact your series has had so far. What do you hope will happen next?

A: Since the series came out, a New York City Council member and a New Jersey State Assembly member have introduced legislation that would create or increase penalties for people caught selling, driving with, or possessing fraudulent temporary license plates. A Georgia House of Representatives member said he will introduce a bill on the issue as well when the state legislature reconvenes next year. And the New Jersey Motor Vehicle Commission appears poised to propose new rules that seemingly would expand its powers to go after temp tag sellers and would make it harder for some multi-dealer locations to operate.

If states want to eliminate this problem, my reporting suggests they will have to cut it off at the source: make it harder to open a sham used car dealership and print temp tags with bogus information. It’s not rocket science: many states simply do not have this problem because they regulate used car dealers and license plates more stringently. And Texas, once the epicenter of temp tag fraud, has made major strides toward rooting it out, including recently enacting legislation that will phase out the state’s paper license plates entirely.

Q: Did anything funny or unusual happen while you were reporting this story?

A: One episode sticks out: visiting a Staten Island car dealership that consisted of a fenced-in wedge of land, a trailer, and an unfriendly German Shepherd. When I identified myself as a journalist and asked the manager about the unusual number of temp tags being printed by an affiliated dealership in New Jersey, he asked me if I worked with the government, threatened to sue Streetsblog, and suggested there’d be “trouble” for me if I looked into his business. That caught my attention, of course, so I did look into his business and included what I found in the series.

Q: Every successful investigation teaches you something that you’ll carry forward to your next assignment. What did you learn from this project?

A: This project was a good reminder to take hunches seriously. I noticed something odd, I couldn’t stop noticing it, so finally I looked into it. Turns out, these innocuous-looking paper license plates were the products of a vast, underground economy that had been operating largely in the dark. Sometimes the hunches are right.