Moshe Marvit Wins March Sidney Award for Profiling the Most Exploited Workforce You’ve Never Heard Of

Moshe Marvit wins the March Sidney Award for his Nation magazine profile of the hidden world of crowdworkers, digital pieceworkers who earn an average of $2-$3 an hour at home, performing repetitive “microtasks,” such as transcribing words from photographs, analyzing snippets of text, and judging whether images are pornographic. Nobody knows exactly how many of these workers exist, but millions of people in the United States and around the world do crowdwork at least part time.

Crowdwork customers range from large companies like Twitter to individual web surfers. Brokerages like Amazon’s Mechanical Turk and CrowdFlower bring buyers and sellers together and take a cut of the action.

Marvit reveals that, as independent contractors, crowdworkers are not entitled to minimum wage or civil rights protections, even if they work in the United States. As in other low-paid labor markets, wage theft is rampant in cyberspace: a client can simply refuse to pay for completed tasks and an angry client can torpedo a crowdworker’s earning power with a single bad review.

A pending class action lawsuit could help establish the legal precedent that crowdworkers are employees. The suit could cover as many as four million U.S. workers.

“Marvit casts a light on a previously obscure, but profoundly exploited class of workers,” said Sidney judge Lindsay Beyerstein.

Moshe Marvit is an attorney and fellow with The Century Foundation focusing on labor and employment law and policy. His articles have been published in numerous law reviews, The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Nation, The New Republic, and elsewhere.

Backstory

Q: What is crowdworking and how did you become aware of its existence?

A: Crowdworking is work that is procured through the vast anonymous “crowd” made available by technology. The fact that what individuals do is work is too often forgotten or ignored by those who utilize crowdwork. Several individuals I spoke to while researching the article insisted that they prefer to call it “crowdsourcing,” however that obscures the important and unforgettable fact that these individuals are performing labor.

I first became aware of crowdwork and the labor platforms that facilitate it while in graduate school. I heard of colleagues utilizing Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to get survey answers, and I decided to explore further.

Q: What kinds of jobs do crowdworkers do?

A: Theoretically, the crowd can perform any decentralized function and crowdwork enthusiasts often point to NASA’s offering a large bounty to anyone in the crowd that can find a way to forecast solar activity or keep food fresh in space. These tasks look like a traditional bidding process that organizations use routinely, but with a far greater reach. On the low end of the crowdwork market, where the bulk of crowdworkers toil, the tasks and remuneration couldn’t be more different. These crowdworkers perform monotonous and repetitive tasks that computers cannot do. These include tagging photos, looking up local business addresses, taking brief surveys, determining if images are safe for work, categorizing pornography, editing sentences, and anything else that can be outsourced efficiently.

Q: Amazon ushered in the era of crowd working with a 2005 SEC filing. What did they describe in that document?

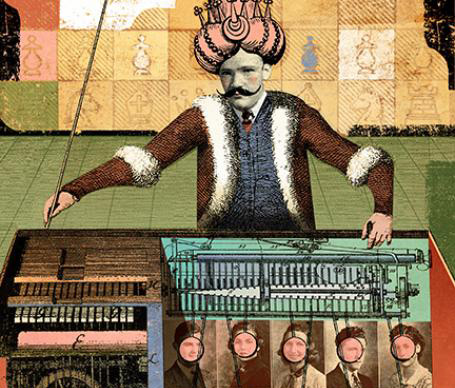

A: In Amazon’s 2005 SEC filing, Amazon offered only a brief description of its new Mechanical Turk project at the end of a list of websites it operates, describing it as simply “a web service for computers to integrate a network of humans directly into their processes.”

Amazon did not actually create the technology or idea behind Mechanical Turk. Rather, Amazon purchased it from another company that called it Agreya, which is Sanskrit for “first.” Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos insisted on changing the name to “Mechanical Turk,” despite concerns by others that the name could invite criticism because it exemplified longstanding western stereotypes of the “Orient.” However, Bezos insisted that the labor platform he was building should be called “Mechanical Turk” because he envisioned a modern analog to the 19th Century automaton—something that feels like a machine to the user, but really has people behind it.

Q: Turkers are exempt from minimum wage, Social Security, and the Civil Rights Act. How is this possible?

A: Whether correctly or incorrectly, crowdworkers are classified as independent contractors. Therefore, they get none of the protections of employees. Additionally, because of the novelty of the technology, many have simply treated this world as the Wild West, where hard-fought labor and employment laws simply do not apply. Employment practices that would be clearly illegal “in real life” (or “IRL” in the acronym-speak of the Internet), are tolerated in the virtual world of crowdwork. Therefore, on Mechanical Turk and other crowdwork platforms, practices such as excluding workers in certain countries or keeping work product but refusing to pay are the norm, even though there are laws that make such practices illegal.

Q: Some experts argue that the Mechanical Turk is a marketplace that’s dramatically rigged in favor of the employer, what do they mean by that?

A: The crowdworker on Mechanical Turk has virtually no rights, and the employers call all the shots. Tasks and rates are determined solely by the employers, and because of the oversupply of labor on these platforms and the need to do many many tasks to make even minimal amounts of money, there are individuals that will perform the tasks. Workers have no rights to relief if they are cheated or their work product is stolen. And there is no such thing as paying too little or requiring free labor to perform a task (such as reading long instructions). This is part of the reason that this labor platform so intrigued me. Many conservatives have been pushing for greater deregulation of labor—such as lowering or eliminating the minimum wage, getting rid of child labor laws, dismantling protections for union organizing—and in Mechanical Turk we can see the world we’d be living in if such deregulation occurred.

Q: Tell us about the lawsuit that might reclassify up to 4 million crowd workers as employees.

A: The lawsuit is by a group of crowdworkers against a major crowdworking company called CrowdFlower. These workers allege that they made less than $2-3 per hour, far less than the minimum wage, and have been misclassified as independent contractors. A proposed settlement has been submitted to the judge, and if he approves it, this case will come to a close. However, there will certainly be more cases like this one, and it may be judges that define crowdworkers’ rights. These workers are anonymous and scattered, so the normal means of lobbying for worker protections through legislatures is unlikely to occur. Instead, the courts will have to engage in the difficult task of applying existing labor and employment laws to the virtual world of crowdwork.