USA Today wins July Sidney for Exposing the Indentured Servitude of California Port Truckers

Brett Murphy wins the July Sidney for “Rigged: Forced Into Debt. Worked Past Exhaustion. Left With Nothing,” published by the USA TODAY Network.

Short-haul truckers, like Samuel Talavera Jr. and Rene Flores, move vast quantities of merchandise from the ports of Los Angeles to rail yards and storage depots. Murphy’s year-long reporting on more than 300 truckers at two ports, which began while he was a graduate student in UC Berkeley’s journalism program, revealed that the industry runs on a modern-day form of indentured servitude.

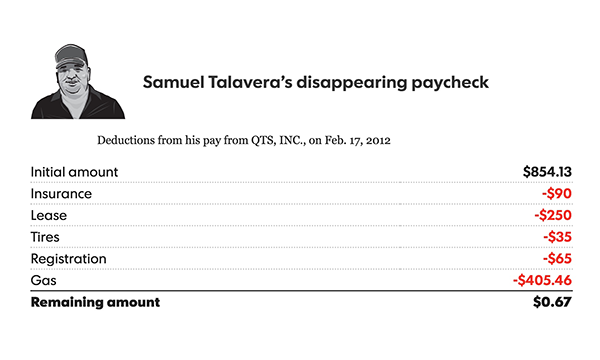

The racket starts with the allure of a lease-to-own agreement for the truck. But, if a driver misses a payment, gets sick, quits or gets fired, they lose not just the truck but every cent they’ve paid into it. Then the company leases the truck to someone else. Some truckers work twenty hours a day, six days a week, just to make ends meet. At times, Talavera earned just sixty-seven cents a week. He eventually lost his truck and the $78,000 he’d paid for it because he couldn’t afford repairs. Some companies have told their employees that they owe them money at week’s end. Some companies physically bar their employees from going home, forcing them to sleep in their trucks.

Flores was fired after being quoted in the USA TODAY story describing how his employers forced him to consistently work illegally long hours and keep fake records to hide the violations. He lost the $60,000 he’d paid towards his truck.

“Murphy’s investigation shines a light on the hidden brutality behind our lowest-bidder, just-in-time economy,” said Sidney judge Lindsay Beyerstein, “He showed how brands like Ralph Lauren, Target, and Home Depot rely on subcontractors who exploit their workers ruthlessly.”

Brett Murphy is an investigative reporter with the USA TODAY Network in Florida, writing about labor and working conditions. He co-founded the Local Matters newsletter, a weekly roundup of investigative journalism around the country. Murphy is 25 and lives in Naples, Florida.

Backstory

Q: How did you become aware that port truckers were existing in a state of modern-day indentured servitude.

A: I first found the story while I was in grad school at the University of California Berkeley’s Journalism School, where I was sponsored by the Investigative Reporting Program. Then my editor Chris Davis at USA TODAY really brought it into focus. He was the key to the project.

The longshoremen were striking on the West Coast, and I was doing some reporting on how that had impacted local businesses. I started talking to truck drivers who were lined up for miles, waiting to get inside the terminals to deliver containers.

I heard from trucker after trucker about the same work arrangement: If they weren’t able to deliver enough containers, they would owe their employer money on Friday and take home nothing to their families. The idea of paying to work while driving company equipment struck me.

I then started reading books and studies about trucking, the ports and deregulation to familiarize myself with the complicated dynamics of the industry.

Q: Your reporting is based in part on contracts that had never before been made public. How did you obtain these documents?

A: The backbone of the whole story is public records and source reporting. Most of all the documents, including those contracts, were buried in files submitted to the California labor commissioner’s office and civil court as evidence and hearing notes.

Many drivers came to the hearings with thousands of documents, including their handwritten daily contracts, which I later received through state public records act requests. I then matched the container numbers in those contracts with shipping records in the Panjiva database.

I also obtained a good chunk of internal records from the drivers themselves. Truckers are diligent record keepers. So I was able to build this investigation from piecing together everything they had kept over the years and then submitted as evidence or passed to me directly.

Q: Port truck driving has been likened to sharecropping. Can you unpack that analogy for us?

A: We brought the investigation’s findings to labor experts all over the country and kept hearing that there weren’t many modern equivalents to port trucking. Instead, experts used phrases like debt peonage, indentured servitude, sharecropping, serfdom and company store.

In those situations, like port trucking, poor workers were targeted to cover the company’s business costs with some form of debt repayment. Companies can use that debt to leverage forced labor.

People like civil rights leaders Julian Bond said the arrangement is akin to sharecropping because drivers work to pay off a truck, like tenant farmers worked to pay off their plot of land in Jim Crow South. In both cases, their employer and landlord is one in the same.

Trucking managers own the trucks their employees are working to pay off. Like an indentured servant, the truckers are bound by the contract, the terms of which often expressly prevent them from working anywhere else. If they get fired or quit, they lose the truck and all the money they had paid toward it.

Drivers can work around the clock all week, but if they’re unable to turn enough containers – because of congestion, traffic, a blown tire, diesel spikes or anything else out of their control – then they can end up in the red, owing their boss money.

Q: How have trucking company owners pushed the cost of environmentally upgrading the trucking fleet onto workers?

A: Another common factor between port truckers and exploited workers in past centuries is a desperate, relatively new labor class. Port truckers are almost entirely immigrants from Central and South America, who faced sudden unemployment after new environmental regulations a decade ago.

These guys used to own their own trucks, old clunkers that belched diesel exhaust into the air. Southern California officials banned them almost a decade ago. Company owners knew their drivers couldn’t afford new, $100,000 clean trucks and realized they were about to lose their entire labor force overnight.

So most of the industry adopted lease-to-own contracts. Companies bought the trucks outright or through third parties and started passing those costs directly through to their workers.

Drivers walked into work one day, and their bosses told them they’d need to sign if they wanted to keep working (they often weren’t offered time to read or a translation.) Ever since, companies have drafted hundreds from their weekly pay to cover the trucks’ costs and maintenance. All the while, they still call the drivers independent contractors instead of employees.

Q: What did you learn in the course of this investigation that you will carry forward to your next project?

A: I learned how important is to organize and keep my notes. This story was a constant circle between data and documents, so it became important for me to track my own evidence. Going forward, I’ll be quicker to build my own databases of people, companies, testimony and evidence.

Likewise, I learned that most public records don’t require a formal FOIA. Building relationships with government record keepers became a new kind of source reporting just as important as those inside trucking companies.

Q: Have there been any important developments since the first story ran?

A: After the first story ran, the Teamsters union staged a weeklong strike at several of the companies we named in the story. Local, city and state officials have publicly denounced the abuses we detailed in the reporting. Some of the retailers we connected to the trucking companies have opened internal investigations into their port trucking operations.

In one of the most concrete developments since we started publishing, one of the truck drivers named in the reporting, Rene Flores, was fired for speaking out about working conditions, criticizing his bosses and refusing to comply with company policies.