Wall Street Journal wins October Sidney for Exposing 131 Federal Judges With Unlawful Financial Conflicts

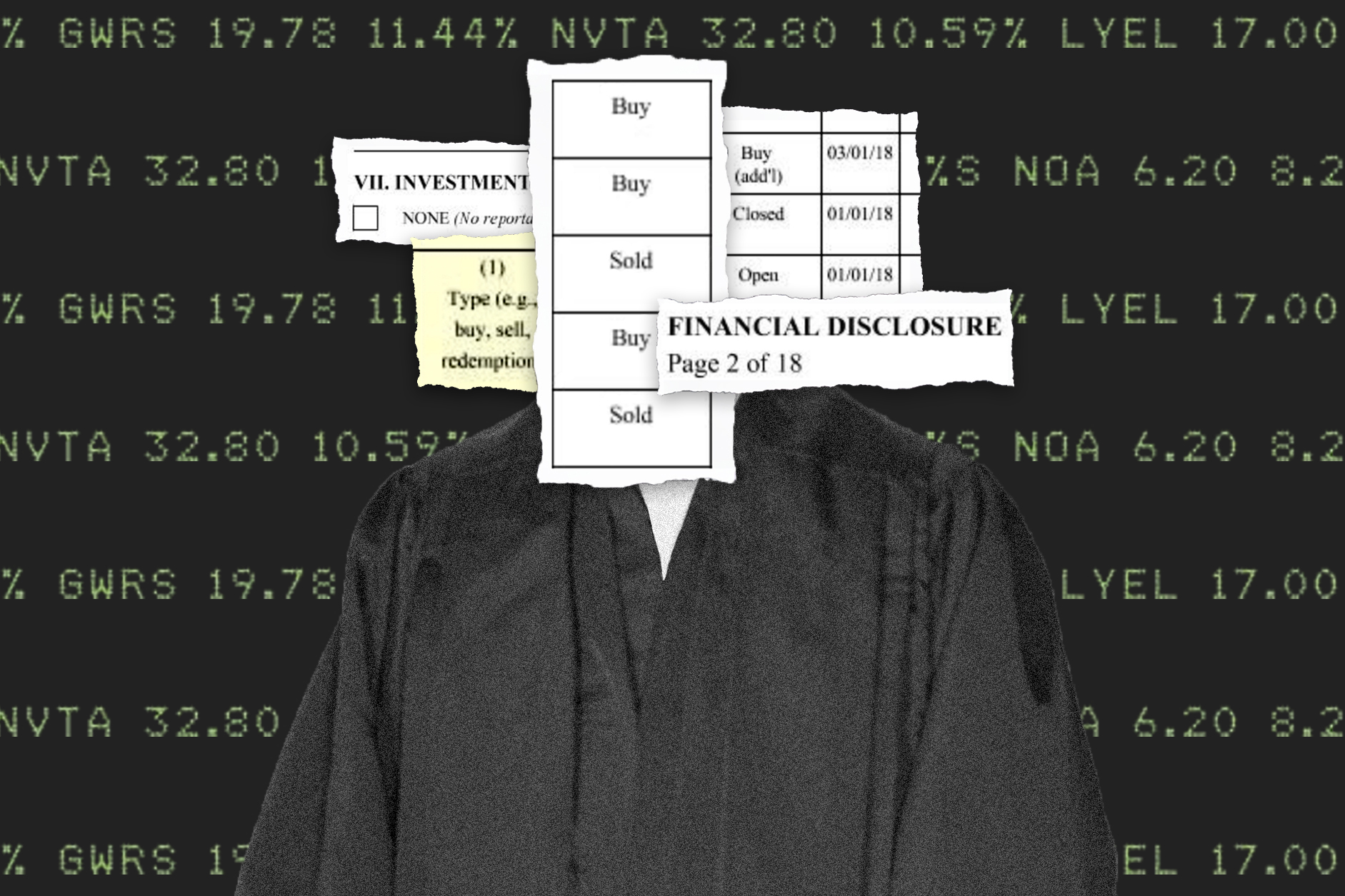

James V. Grimaldi, Coulter Jones, and Joe Palazzolo of the Wall Street Journal win the October Sidney Award for exposing 131 federal judges who ruled on cases despite a financial conflict of interest. They found a total of 685 cases in which the judge had a financial conflict in the last decade alone.

This conduct isn’t just unethical, it’s illegal. A Watergate-era law requires judges to know their holdings and those of their immediate families and to step aside whenever there’s a conflict. Judges’ financial disclosures aren’t online and judges are informed if anyone requests to see their disclosures–which creates a disincentive for lawyers to delve into conflicts of interest, lest they annoy the judge.

“This story exposes an epidemic of casual lawlessness within the federal judiciary,” said Sidney judge Lindsay Beyerstein, “These findings should shake our faith in the impartiality of the system.”

Judge Edgardo Ramos of New York sided with Exxon in a pollution case while he owned up to $50,000 worth of Exxon stock. The husband of Judge Julia Smith Gibbons of Ohio bought $30,000 of Ford stock while his wife was presiding over a Ford trademark case. Judge David Norton in South Carolina presided over six asbestos suits while his disclosures show he held between $95,004 and $250,000 of stock in two defendants, 3M Co. and GE.

A majority of federal judges own individual stocks, and nearly 20% of those who do have heard at least one case involving those stocks. Judges voted in favor of the company in which they owned stock about two-thirds of the time.

The impact of this story began before it was even published: Fifty-six of the judges said they notified parties in 329 lawsuits about a conflict. The number of judges alerting parties has continued to climb since the story came out and now stands at 63. As a result, these cases may be retried by new judges.

##

James V. Grimaldi is a Pulitzer Prize-winning senior writer on the investigations desk and based in Washington, where he has written about government accountability and public and corporate corruption.

Coulter Jones is a journalist on the investigations team who specializes in using data analysis, programming and open records to report compelling stories. Before joining The Wall Street Journal, Mr. Jones worked as an investigative and data reporter for MedPage Today, New York Public Radio, The Center for Investigative Reporting and newspapers in Pennsylvania.

Joe Palazzolo is a reporter on the investigations team. He previously covered national legal affairs for the Journal, focusing on the functioning of the courts, privacy, gun laws and federal law enforcement. Mr. Palazzolo was part of a Journal team that won the 2019 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting.

Backstory

Q: How did you decide to investigate federal judges hearing cases where they had financial conflicts of interest?

A: Federal judges, who are appointed for life, get very little scrutiny outside of news stories about what goes on inside the courtroom or cases heard on appeal. They rarely speak to the press or the public and are unaccustomed to anyone obtaining or ever seeing their financial disclosure forms. So when I heard that all federal judges’ financial disclosure forms would become available in a digital, searchable form for the first time, I knew there could be an investigative project in there.

About the same time Coulter heard about an academic study using incomplete financial disclosure data from a decade ago, which found that some judges had failed to recuse themselves. Both Coulter and I report to Investigations Editor Mike Siconolfi and he asked us to team up and develop a methodology to see if judges still broke the law or had cleaned up their problems. Mike brought in Joe, another member of Mike’s team, because Joe had extensive experience covering the federal courts at the Journal and other publications.

Q: Give us a sense of the scope of the problem you uncovered?

A: The Journal found judges failing to disqualify themselves as required in every region of the country. They included judges appointed by nearly every president from Lyndon Johnson to Donald Trump.

When there were contested motions in cases involving companies the judges had a financial stake in, two out of three of their rulings on the motions were in favor of those companies.

Dozens of judges or their families not only owned shares in companies in their courtrooms but traded the shares while the judges were presiding in the cases.

Legal experts said the activity the Journal found amounts to a pervasive disregard for the judicial conflict-of-interest laws. Indiana University Law Professor Charles Geyh said that, in isolation, a violation could be viewed as an oversight. But the Journal’s overall findings raise “a more systemic problem of judges chronically neglecting their duty to disqualify in such cases.”

Our investigation is continuing.

Q: Can you give us an example or two of the conflicts that you found?

A: Judge Rodney Gilstrap has taken on 138 cases since 2011 that involved companies in which he or a family member had a financial interest – more than any other federal judge – our investigation found. The companies included Microsoft Corp. (53 cases), Walmart Inc. (36 cases), Target Corp. (25 cases) and International Business Machines Corp. (9 cases).

The chief judge for the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas, Judge Gilstrap also disclosed one of the largest holdings in a conflicted company. He oversaw a patent-infringement case against a Walt Disney Co. unit while he or his wife reported holding between $100,001 and $250,000 of Disney stock. The plaintiff later withdrew its claim.

In New York, Judge Edgardo Ramos handled a suit between an Exxon Mobil Corp. unit and TIG Insurance Co. over a pollution claim while owning between $15,001 and $50,000 of Exxon stock, according to his financial disclosure form. He accepted an arbitration panel’s opinion that TIG should pay Exxon $25 million and added $8 million of interest to the tab.

Judge Ramos was unaware of his violation, said an official of the New York federal court, because his “recusal list”—a tally judges keep of parties they shouldn’t have in their courtrooms—listed only parent Exxon Mobil Corp. and not the unit, whose name includes the additional word “oil.” The official said the court conflict-screening software relied on exact matches.

But the unit had informed the court at the outset of the case that it was a subsidiary of Exxon Mobil so Judge Ramos could “evaluate possible disqualification or recusal,” a court filing shows.

Q: The law says that judges must familiarize themselves with their family’s assets and recuse themselves whenever there’s a conflict. Why have so many judges gotten away with ignoring the law?

A: Violations of the 1974 law almost never become public. Judges’ financial disclosures aren’t online, are cumbersome to request and sometimes take years to access. We are still waiting for forms filed by judges for the calendar year 2019.

Judges are informed if anyone requests to see their disclosures, creating a disincentive for lawyers who might fear annoying judges in whose courtrooms they frequently appear.

Judges rarely make public their recusal lists – the lists of individuals and companies on whose cases they shouldn’t work. When judges disqualify themselves from cases, they typically don’t disclose details. No judges in modern times have been removed from the federal bench solely for having a financial interest in a plaintiff or defendant that appeared in their courtroom.

Q: What impact has the investigation had so far?

A: Our investigation led to many judges admitting their violations of the law. After being alerted to violations by the Journal, 63 judges have directed court clerks as of Oct. 6 to notify parties in 365 lawsuits that they should have disqualified themselves and that cases could be reassigned and reopened.

In the case before Judge Ramos involving Exxon Mobil Corp., lawyers for the losing party that had sued a unit of the oil company now have asked an appeals court to toss out the ruling and order a review by a new judge because of “the inevitable appearance of partiality that results from these unfortunate circumstances.” The court clerk, in a notice prompted by the judge, said the judge’s Exxon holdings didn’t have a bearing on his ruling in favor of the company.

In another case in an Alabama federal court, a judge ruled against two homeowners in a foreclosure case against Wells Fargo & Co. The judge had bought Wells Fargo stock about two weeks after receiving the case. “This is outrageous,” one of the homeowners said when told the judge held the bank shares. “How am I supposed to know she owns stock in Wells Fargo?”

Q: What did you learn from this project that you will carry forward to your next investigation?

A: Collaborations with nonprofit organizations are worth the effort even if working out the details takes time and effort. Seek guidance from academics and other experts on the law and methodology on complex projects. Finding the right team that can pull off a project requires the right chemistry and mix of talents that complement one another. Provide the subjects of your investigation plenty of time to respond. The Journal’s “no surprises rule” made the story better. In this case, the comments from judges, and the subsequent court filings in their cases, were nearly as revealing as the findings themselves.